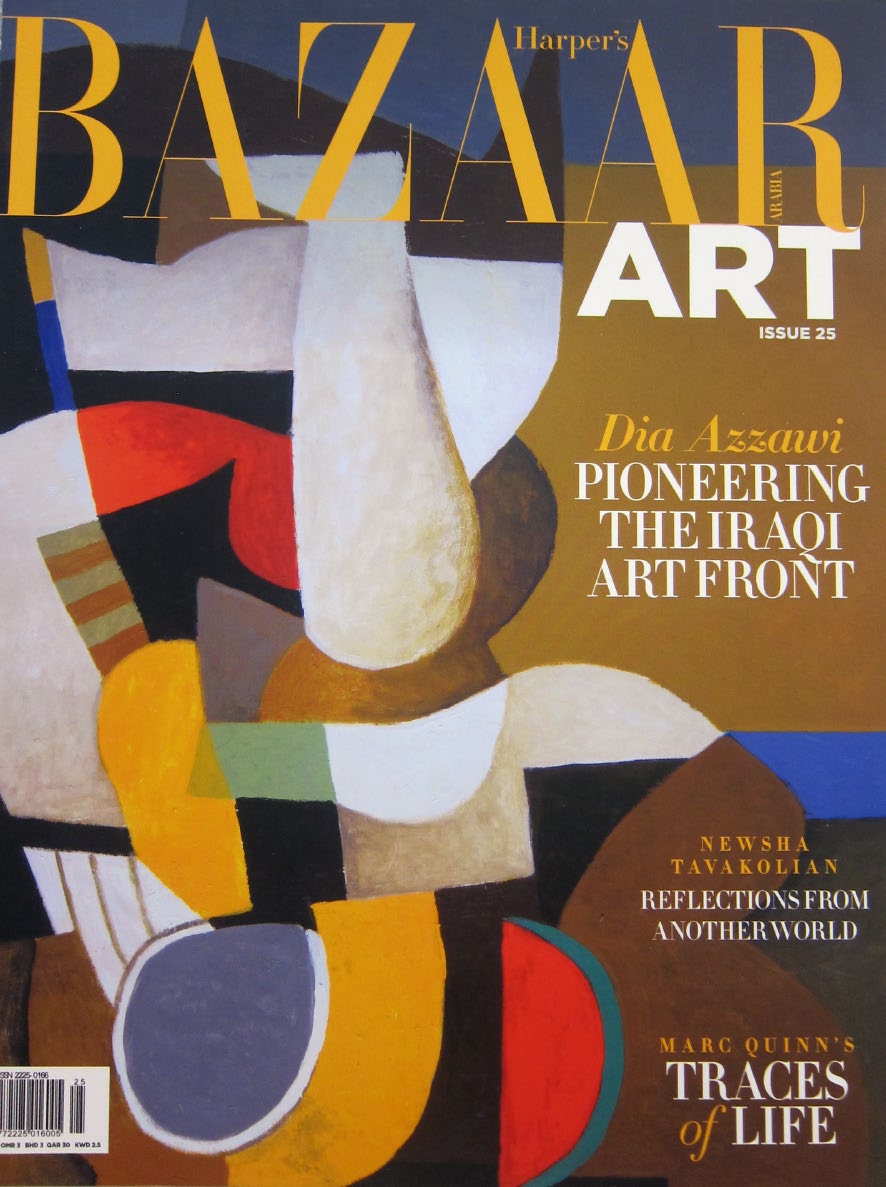

by Glynn Pogue, Fjord's Review 2016

Read MoreThe Radiant Child by Rene Ricard, Published in Artforum /

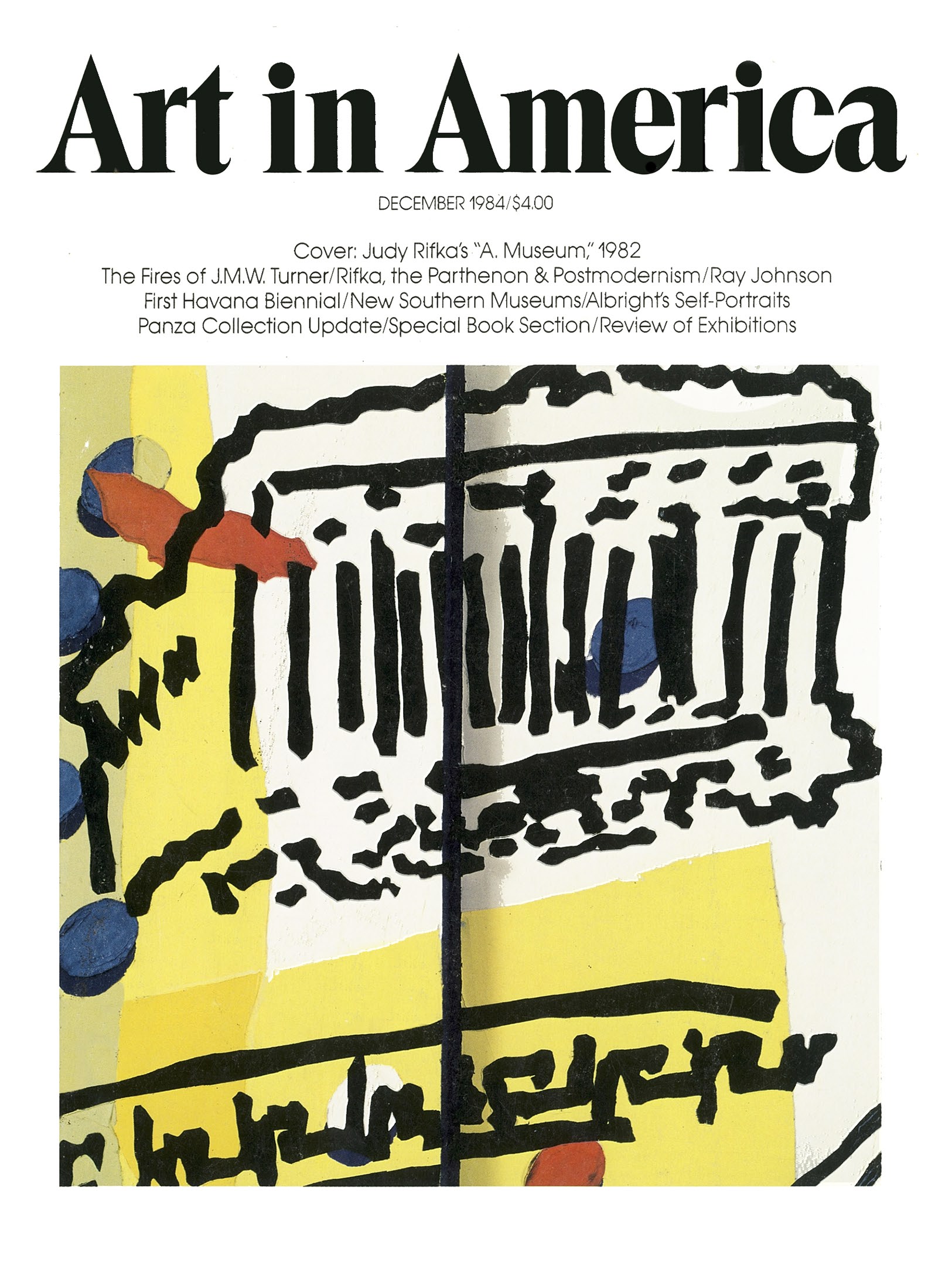

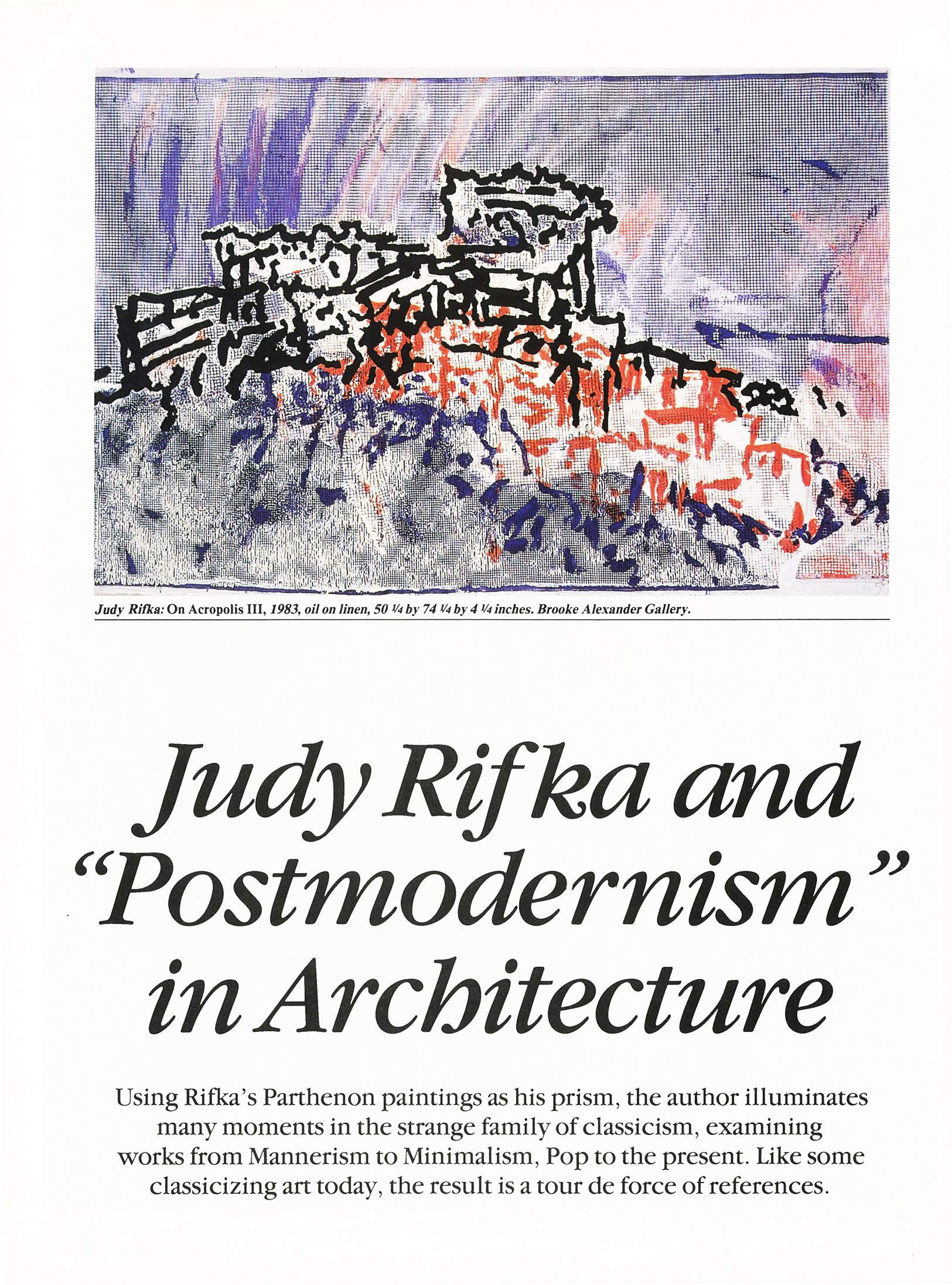

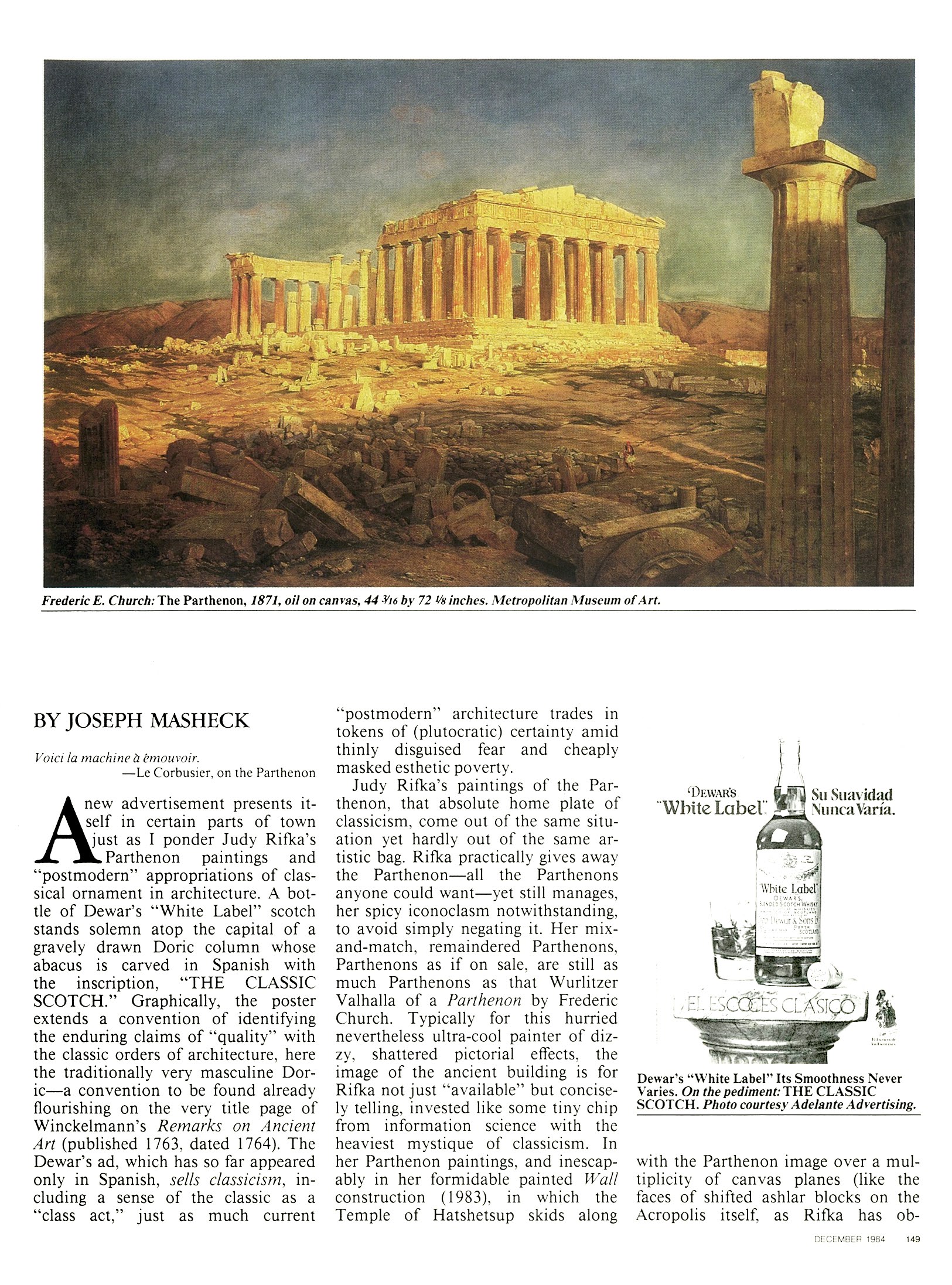

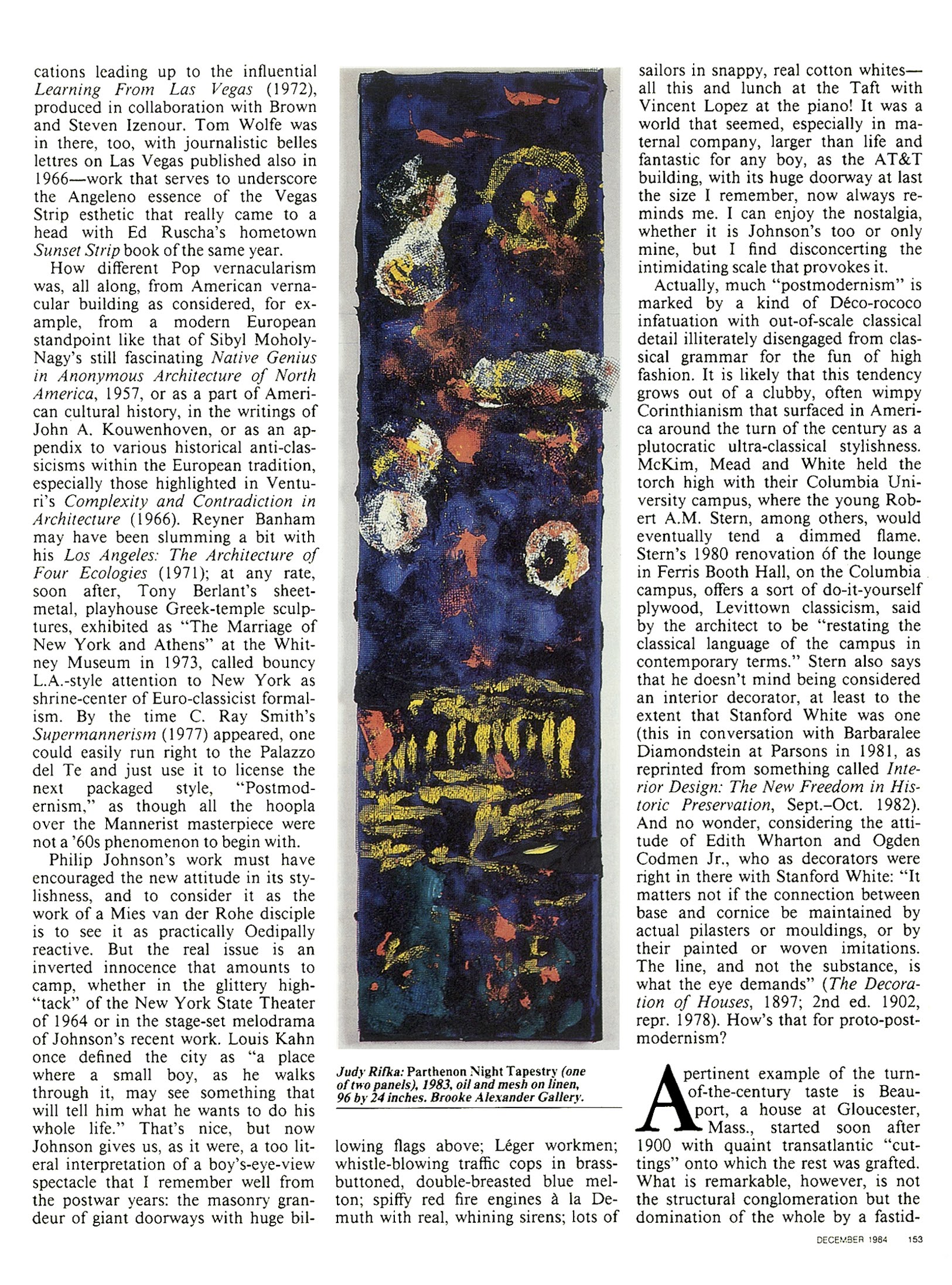

Judy Rifka And "Postmodernism" In Architecture /

The Greatest Show On Earth: An Essay by Rene Ricard /

The Radiant Child: Judy Rifka and her Continuing Spirit-Dance with Postmodernism – by Gregory de la Haba 2017 /

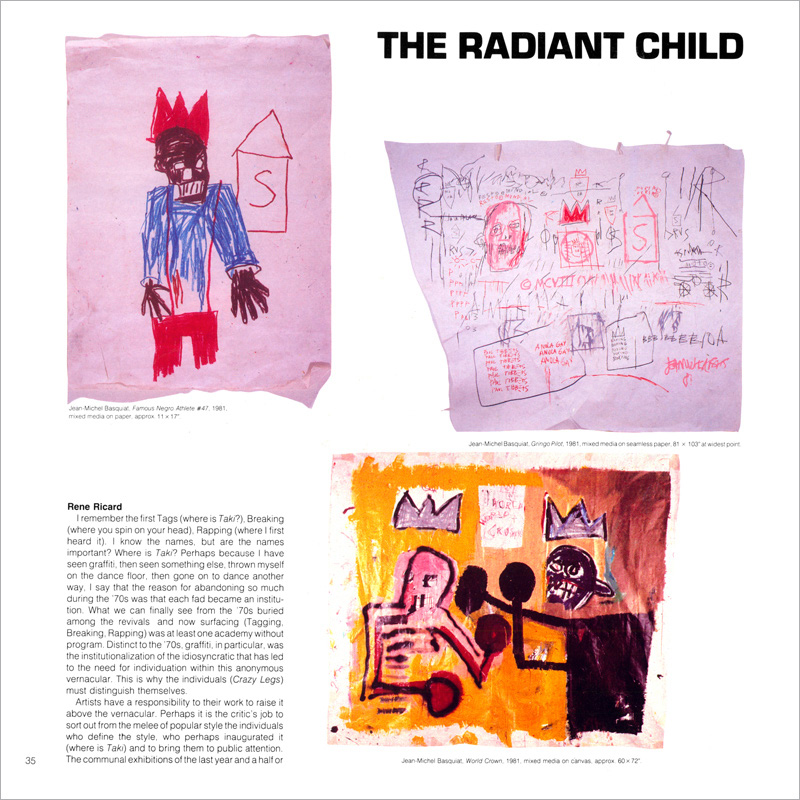

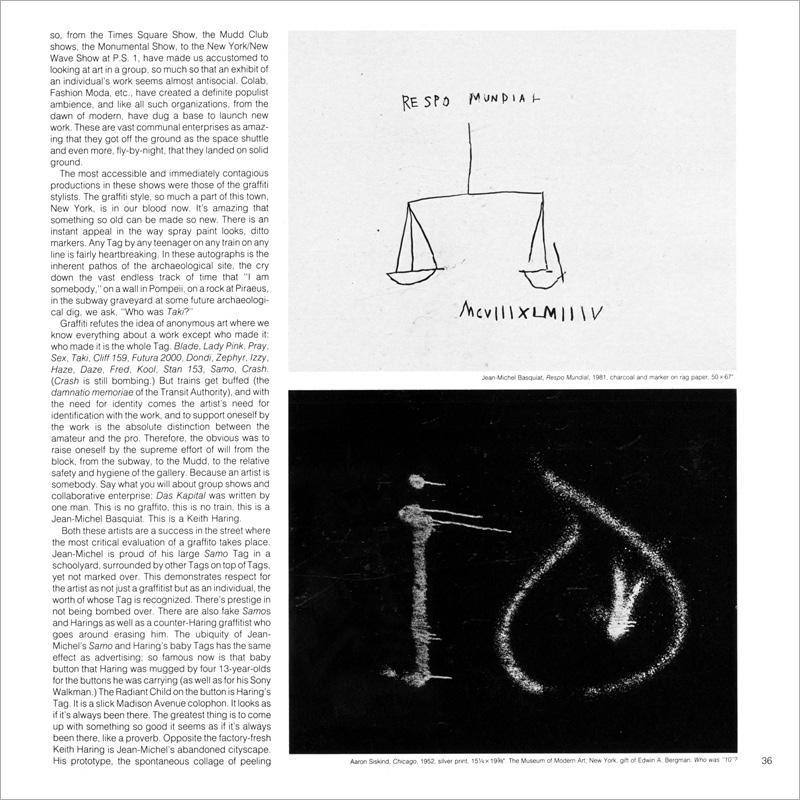

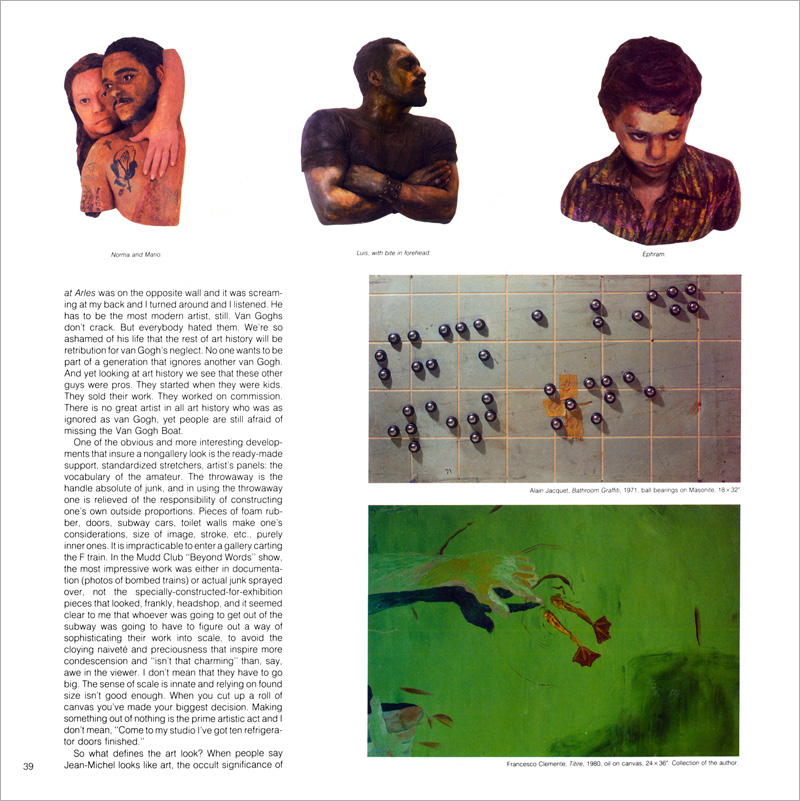

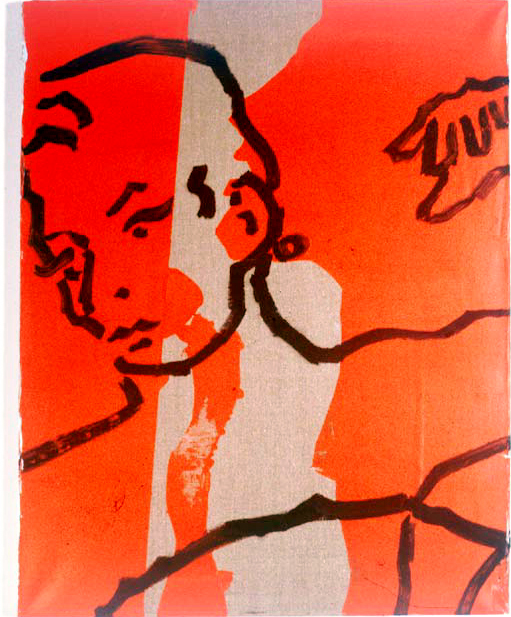

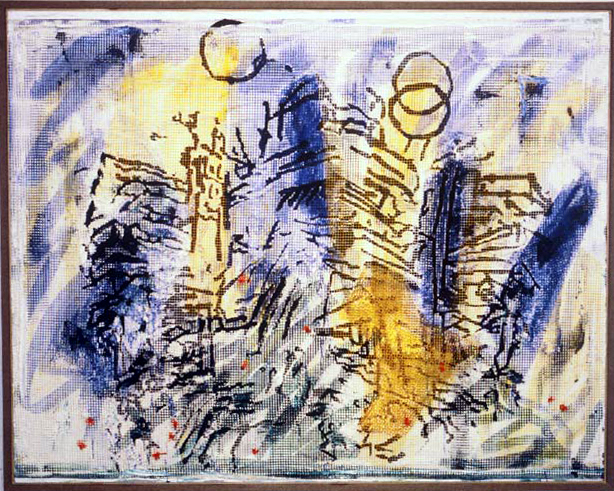

In his oft-cited Artforum article, Rene Ricard (1946 – 2014) wrote on the importance of becoming one’s name, on being original, innovative, and by personifying the artist-as-icon role in the public realm. For the last fifty years, Judy Rifka has continued to personify that statement by existing both within the zeitgeist and on the periphery of it—even, at times, falling out of favor from it (it happens when you live a long and fruitful life)—all the while ceaselessly challenging her own modus operandi, her art and art forms that include painting, sculpture, video, performance, and more recently, Facebook and Instagram, those vast new canvases of social media Rifka embraces fully to dialogue with thousands of her adoring fans worldwide. Ricard wrote: “One is at the mercy of the recognition factor and one’s public appearance is absolute….If Andy Warhol can’t be used as an object lesson in how to become iconic then his life has been a waste. We become our name.” And in this very public arena, Rifka, the quintessential archetype of a generation of art giants—many lost to drugs and AIDS—that emerged on New York’s downtown scene in the 1970’s, becomes Rifka the modern-day social media artist who shares, posts and ‘LIKE’s via daily ritualistic performances– and they are performances, executed as if on Ricard’s cue–to boost ‘recognition’. A restless spirit with a Postmodernist, punklike soul, Rifka set forth as artist during the heyday of the Age of Aquarius, the hippie generation in the midst of political chaos, Vietnam, and excitement at every turn. Her pro-action mindset in such an environment allowed Rifka to explore love and art simultaneously, easily, and with Abstract-Expressionism as guide and Flower Power as bar, boundaries in paint and life were pushed to the limits. Exploration became de rigueur of the day and from the moment she first stepped on the New York art scene as full-fledged artist in the early 1970’s, Judy Rifka became her name and would, before long, become The Radiant Child:

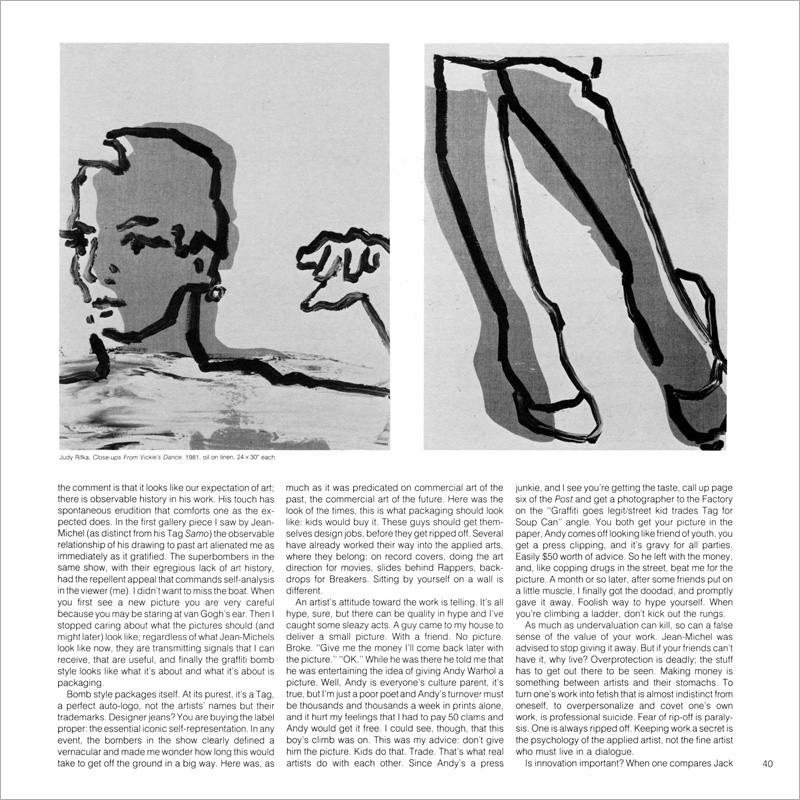

“Rifka’s work at the debut of the ‘70s…. her single shapes on plywood are among the most important paintings of the decade. Every painter who saw them at the time recognized their influence.”

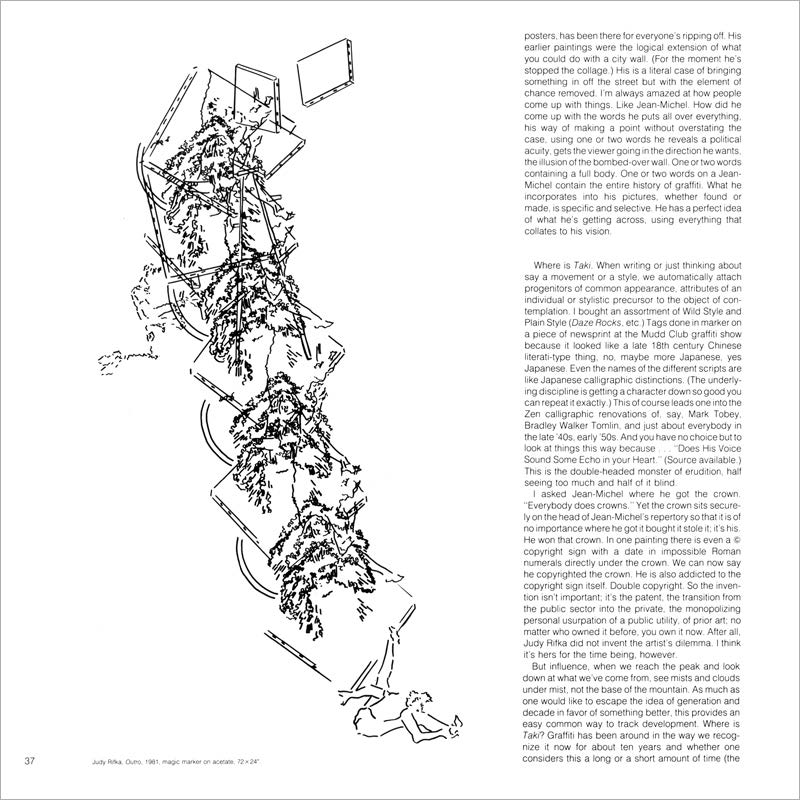

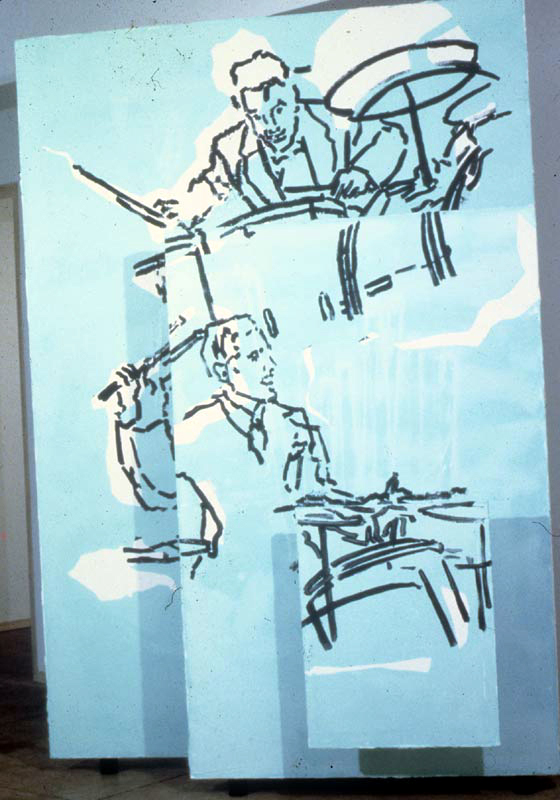

Rifka asserts she should have been an sculptor for she was “more interested in developing form than continually relating spatial arrangements to four edges of a canvas.” These early investigations with form and space would become her raison d’être: “I immersed myself in finding out about space. That really captivated me, trying to understand space, how to see it and how to draw through the image… I traveled through the Southwest and lived on a Navajo reservation where I painted. Desert space became a big thing for me, because there I was, trying to understand space in this vast area. Later, I became involved in dance and mixed the idea of movement with space, considering a line as a trajectory of movement. So it became about understanding space on the two-dimensional plane.” Rifka aims to capture line and forms positing in space as well its trajectory in space and its concomitant wake reverberating outward and within the four-walled holding cell —the 4'x4’ plywood panel used most often for these single shape paintings. These simple yet majestic forms are allowed to ‘dance’, she says, on the panel and by way of layering and building-up of handmade paint they slowly and painstakingly emerge as ‘morphing fields’, a body-form that ricochets within and without and builds momentum, a centrifugal-like force that emanates off the picture plane and exists markedly, agelessly, in the face of Postmoderism’s gaze. This movement dictates direction and hence allows the form to dictate design, starts designing itself, and trajects forward. Judy explains it thusly: “It’s a real different look at space. I’m not really going in the direction of other painters in terms of focusing on the surface and the strokes. I’m really rushing past that to what’s going on in the space and how it’s developing with time. That’s why I’ll often have a shape on the canvas that fairly ignores the exterior. That’s why I liked the plywood; it was like a floor for the shapes to dance on. My compositions often move forward more and laterally incidentally, whereas typical compositions think about the way a viewer is going to relate to the exterior rectangle. I’m just leaving it there as a floor and moving forward.”

Rifka’s single shapes blow past Kasmir Malevich’s Constructivist ideas about space by eliminating entirely any referential or emotionally conjured ideas about space. These works retain too that pictorial flatness Clement Geenberg salivated for. The art critic Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe took note (while also noting how specially unique he found them) in an Artforum article in 1974:

“Judy Rifka’s paintings dominated the show. Rifka’s paintings are flatter than almost any other work that comes to mind, including that of others — Robert Ryman, for example — who are concerned with the material qualification of the painted object. At the same time they suggest a space infinitely deep, and its the scope of this evocation and accommodation of paradox of a subjectively considered material dialectic — which leads me to say that Rifka’s is the most devastatingly original formulation of painting’s identity that I’ve encountered in some time.”

Fast-forward 40 years for a perfect example of historical curation not paying attention, not recognizing, their 70’s darling: In a February 2007, New York Times review of High Times, Hard Times: New York Painting, 1967-1975, Roberta Smith writes of the ‘brave if deficient show’: “In other instances the selected works are minor, as derivative now as they were then. Or the ideas are so literal or reduced that the artists couldn’t go anywhere with them. Some inclusions seem almost ludicrous, given certain rather obvious absences… of Judy Rifka, Bill Jensen or Gary Stephan, whose efforts… were among the most closely watched developments of the early ’70s.”

How wonderful and apropos for Roberta Smith to point out Judy Rifka’s absence from this historical survey. Closer inspection, however, more telling: Rifka’s ex-husband, the artist David Reed – currently showing at Gagosian in New York – proposed that show and was–along with Independent Curators International–behind organizing it. The zeitgeist only human after-all. Slight aside, life goes on and Ms. Rifka, formerly Ms. Tenenbaum, modeled in 1968 for Alfred Leslie’s iconic painting, Pregnant Tenenbaum, created while the young Rifka was carrying David Reed’s son (novelist John Reed) and a student at NewYork Studio School, keeps pushing, keeps moving along. The mid-sixties found Rifka in London living for a month with folksinger Donovan as he was composing “Season of the Witch” and Hunter College beckoned too where she studied with Ron Gorchov whom she’d meet-up again for two years in the 70’s–this time out-of-school–as he was working his ambidextrous saddle paintings and she her single shapes on plywood. Rifka’s movement remains constantly in flux and all the little anecdotes of past times and place important and relevant to the bigger picture–to the layering and building of Rifka’s spirit—and how she carried that spirit with her wherever she went—in every decade—whether it was to Danceteria from ‘79-’86 to showcase her early video work or to Dubai last September for her Retroactive exhibition at the Jean-Paul Najar Foundation, Rifka brings it. Just like she brought it to Tompkins Square Park to have long talks with artist David Wojnarowicz or to Fun Gallery to share (in person) with friend Patti Astor whom she painted in a work titled “Constructivist Nightlife” that Ricard declared: “The Modernist stylizations had come to life.” She brought it to the fourth floor of the notorious Mudd Club where Keith Haring curated and hung her paintings side-by-side with his and where Ricard first saw Rifka’s works and he recognized their importance immediately just as he was the first to recognize Jean-Michel Basquiat and write about him critically for the first time in the very same article The Radiant Child cited above. Yes! That article was as much about SAMO as it was about Haring and Ahearns and Van Gogh and the one and only, Judy Rifka. If the German philosopher Georg Hegel were around today, he’d proclaim affirmatively that Rifka is beyond doubt the absolute geist ihrer zeit (spirit of her time). With emphasis, of course, on the ihrer. And the best part? Her time is now. —Gregory de la Haba

Judy Rifka’s career spans over 50 one-person shows and countless exhibitions; her work can be seen in numerous museums and foundations throughout the United States and Europe and has been featured at the following: 1983 Whitney Biennial, 1975 Whitney Biennial; The Museum of Modern Art, New York; Documenta VII, Kassel; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Carnegie Mellon University; Institute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia; The New Museum of Contemporary Art, New York; The Brooklyn Museum; The Aldrich Museum of Contemporary Art Museum, Ridgefield; Moderner Kunst, Vienna; Laforet Museum, Tokyo; Kansas City Art Institute; The Hudson River Museum, Yonkers; Kunst Rai, Amsterdam; Mint Museum, Charlotte; Bass Museum of Art, Miami; The Museum of Fine Art, Boston.

Huffington Post: Facebook as an Artistic Platform: An Interview With Judy Rifka by James Scarborough 2013 /

This is the second of an ongoing series of interviews with artists who have specifically used Facebook in some manner to expand their artistic practice. The first was with Jennifer Reeves. Los Angeles artist and arts blogger Tracey Harnish, in discussion with Oliver Wasow, has also investigated the impact that social media has had on creativity, documentation, and the very definition of art itself. It should be noted too that the idea for the project came from scrolling down my own wall.

It goes without saying that Judy Rifka is both art historically significant and present-day relevant. Her pre-Internet career spans two Whitney Biennials, Documenta 7, the fabled 1980 Times Square show, over 50 one-person museum and gallery exhibitions, and international museum collections.

Now, in the era of the Social Web, she continues to make art that is smart, witty, and funny, work that appears in various iterations on her Facebook wall (Think of it as her “Judy Was Here” version of the Kilroy meme). Writer Andrea Scrima calls these pieces “quotidian interventions,” which serves as a spot-on description of the way Facebook scrollers discover them, like Donatellos among the Fauves, amidst the digital detritus of the Facebook scrum.

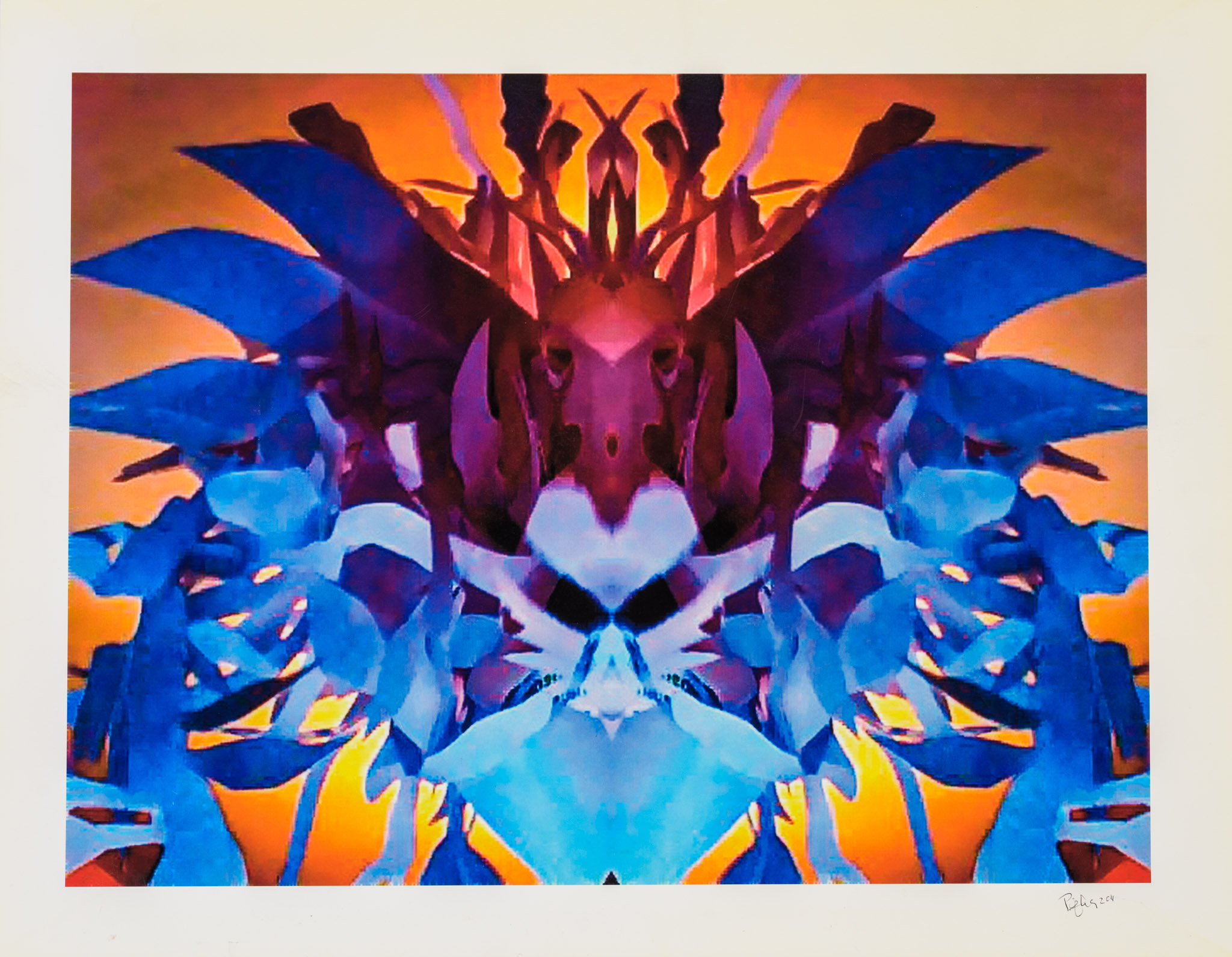

One of the benefits that Facebook-as-artistic-platform confers upon artists is the ability to not just discover what artists are doing (less virtuous artists would call it spying) but to set up the chance for collaboration. Such is the case with a recent series of paper pieces that Rifka created, pieces that were similar in structure to pieces from her “Monster” series. Writing of the “Monster” series, Scrima describes and contextualizes them thusly:

“Rifka seems to take her creations through the various pupal and nymphal stages of metamorphosis and all manner of sexual and asexual reproduction, yet amidst these celebrations of mitosis and meiosis, the artist’s true mode d’emploi is parthenogenesis: she creates and recreates herself at will.”

Because she “creates and recreates herself at will,” the thrust of this interview will be the manner in which these pieces were reborn, via a Facebook encounter with artist and musician Daniel Dibble, into a series of videographed vignettes (see links below).

JS: How did you begin to use Facebook as an artistic forum? How long were you on Facebook before you realized it might offer creative opportunities?

JR: From the start, I thought of FB as an arts platform. I was so happy to have direct contact with people, to show them what I was doing. It solved the problem of having work sequestered in my studio.

Facebook came to life for me in a 2008 thread involving Oliver Wasow, John D Monteith—likely Jennifer W. Reeves was there. It was a quiet summer holiday, and we bantered for two days. By the time the thread ended, I started actively pursuing the forum.

From that time forward, I thought of the platform in two parts: my posts, and my participation in threads.

One FB friend, John D Monteith, gave me a wise tip early on: “Smart and Funny.”

I breathe art. It’s part of my day. I want it to be public without mediation. That is to say, without separation, or gatekeeping, or financial barriers. Just intuition. Maybe a process of intuition comes with years of life in the studio. And I will ask myself: how do people define art in ways that it doesn’t have to be defined? I want to laugh, read The Diamond Sutra. I am intrigued with paradigm shifting.

A few years ago I taught courses on the Golden Age of Athens. It was there that I looked at the development of tragedy. I began thinking about FB comments as a form of Greek Chorus. So you make your posts. Your art. Then the chorus chimes in. They agree. They disagree. They interpret, they give insights. At his trial, Socrates claimed that he always listened to his oracles. That’s how I want to work.

In Jürgen Habermas’ “Ideal Speech Situation,” the public sphere is “a discursive arena that is home to citizen debate, deliberation, agreement and action.” Everyone, and I mean everyone, is allowed to participate, and I adopted that as my credo. I want what Shirkey calls “One Stop Shopping.” In art.

JS: How would you assess the significance of the intersection of your studio practice with the seemingly limitless parameters of social media?

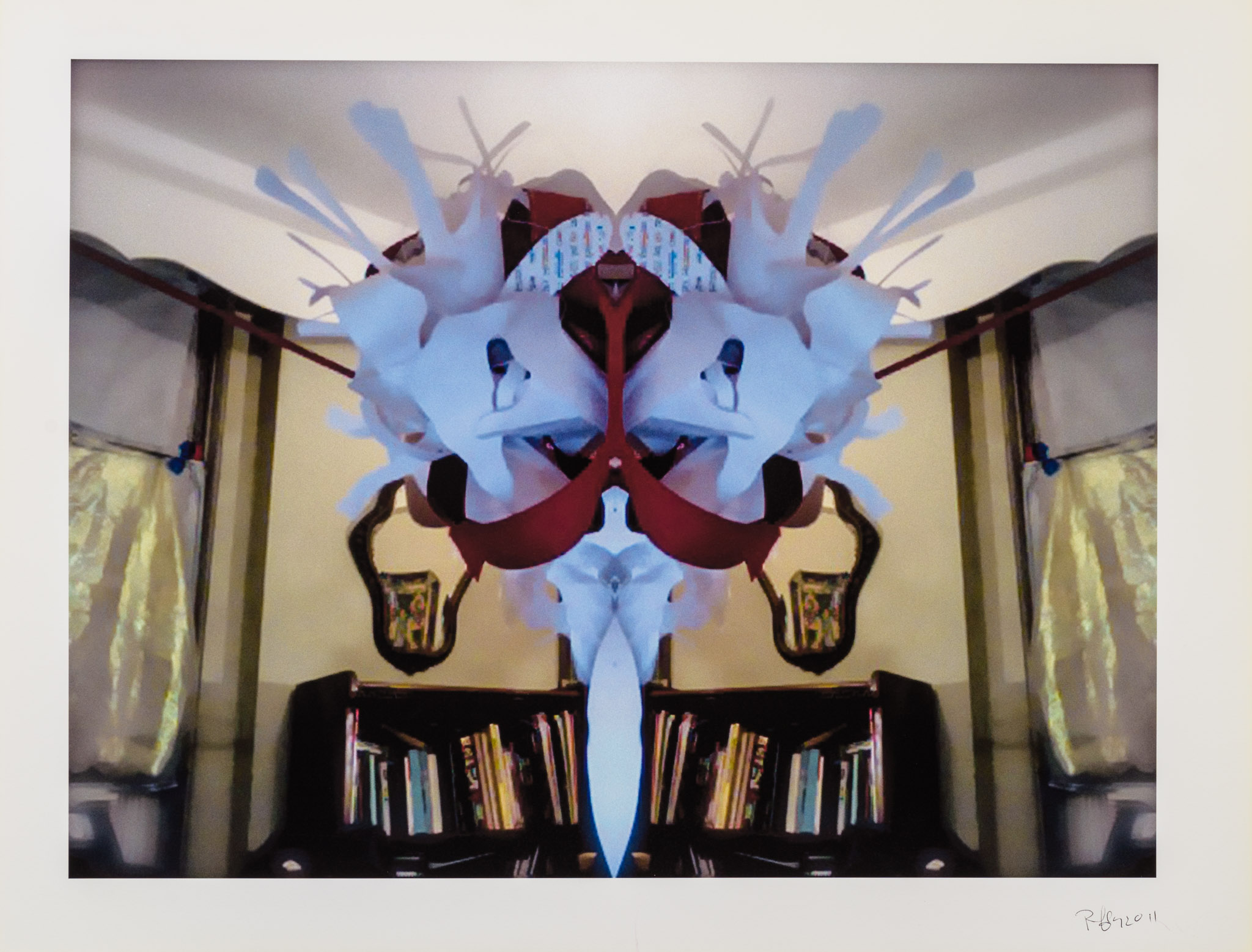

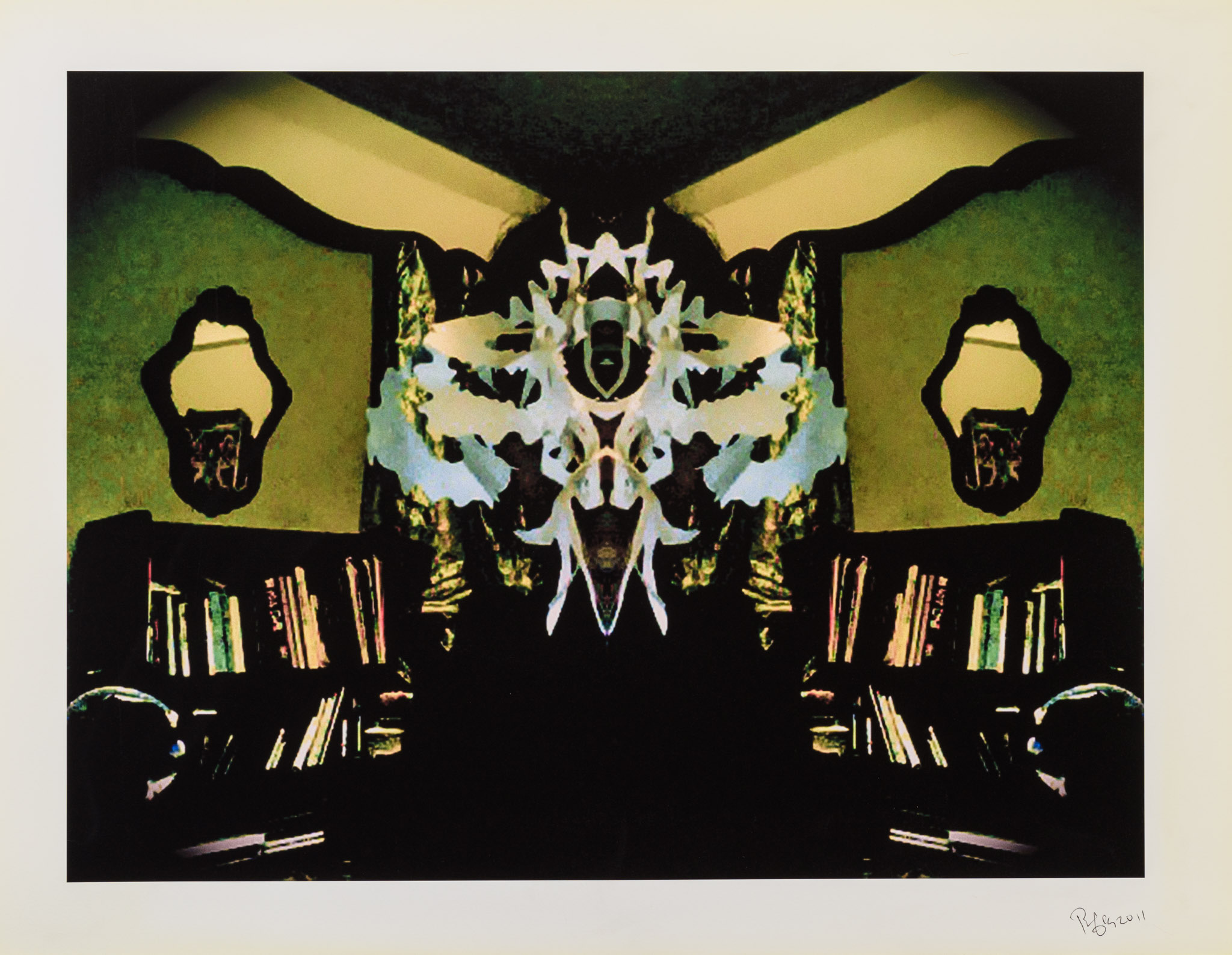

JR: At first, I posted works from my studio. But it wasn’t long before I was using my webcam to show the art as it happened. For the best part of four years, most of the work has been ephemeral. I’d grab a gaggle of papers I had cut, and hold them in front of the webcam, often mirroring, and shoot the moment that captivated me. Sometimes I colorized. Then I’d share and post. People responded with their Rorschach interpretations. So I was live. I wasn’t making things. Only later did I enlarge the “Monster Photographs,” for example, that I showed at “Art 6” and Pool Art Fair. Jennifer W. Reeves and I sat at her magic giant printer, and she helped me produce the prints. But the cut shapes of paper that went into these designs remained detritus on my floor. It would be three more years before I actually pasted the shapes into collages. I think the spontaneity is what “stuck.”

I have to thank both my grown sons, who as kids gave me my best ideas... John, who told me I should do two paintings in one painting, and Matt, whose play school collages stacked papers on top of each other without a care about lateral composition.

JS: What space do you inhabit when you post on Facebook? Is it the equivalent of working alone in your studio with a couple hundred of your best friends? Is it a social cum aesthetic hybrid? Is it something altogether different?

JR: The platform is a giant squid, inextricable from my artistic process and social communication. When it came to the portraits, I wanted people to see my face now. What I look like now. I don’t want to shock or disappoint people when I meet them in 3d!

JS: What were your initial thoughts when you initially began to post your daily photographic self-portraits, images of works in progress, and this collaboration with Daniel, of which more later? Was your initial interest more documentative or did you see at the time that it offered the potential for something different?

JR: The Prof picture itself becomes an avatar. That is who people are talking to. I like to change it frequently, as I redefine and restructure my morphing identity. It is my interactive mirror. A cross between real life and gaming. You friend, you defriend, you flash your visual messages. You comment, you share friends and ideas. The acts are real, but everything takes place on stage.

JS: Even if Facebook goes sideways (it happens), has the era of the Social Web had had a significant and long-lasting impact on art or even particular genres of art, on politics, on the marketing and sale of art? How?

JR: If social media goes sideways, it will be a sad day for democratic and inclusive art and politics.

With social networking sites (SNS) the hegemonic gatekeeping processes and control over the spread of art information is essentially over. Antonio Gramsci (“Prison Notebooks”) would have loved this. He had to write from jail. He should have been on FB implementing OWS (Occupy Wall Street). I’m sure a lot of people try to demean SNS for that reason. People want to laugh at Gramsci or Benjamin, but they were so prescient.

JS: In terms of your creativity and production practice, does the experience of using Facebook as an artistic platform differ from that of your pre-social media era? If yes, how? In terms of feedback (read criticism), does the experience of using Facebook as an artistic platform differ from the pre-social media era? Do you find that the comments and feedback are useful?

JR: It’s not only FB, it’s also the live performance, posting that for all to see, and comment on. That is very different from poring over a Photoshop document and designing a composition. How handy to be able to play music to it on my mac and record the operation! It’s reality art. How clunky and burdensome seem the traditional means of creative communications! Studios, materials, acceptance to limited gallery space, transport, rent! And how all that impacts the criticism process. This is a methodology that’s unencumbered.

Sometimes a piece is a smash hit, sometimes it’s embarrassing, sometimes it’s painful. But you keep going along the moving sidewalk that is Facebook. And the aspect of showing works in the continuum of time informs the process.

JS: Is Daniel a Facebook friend or did you know him prior?

JR: I always laugh when I think about how I saw Daniel on the thread of a mutual friend. That’s pretty much the way it happened. I asked if I could use his Reverbnation and Soundcloud compositions.

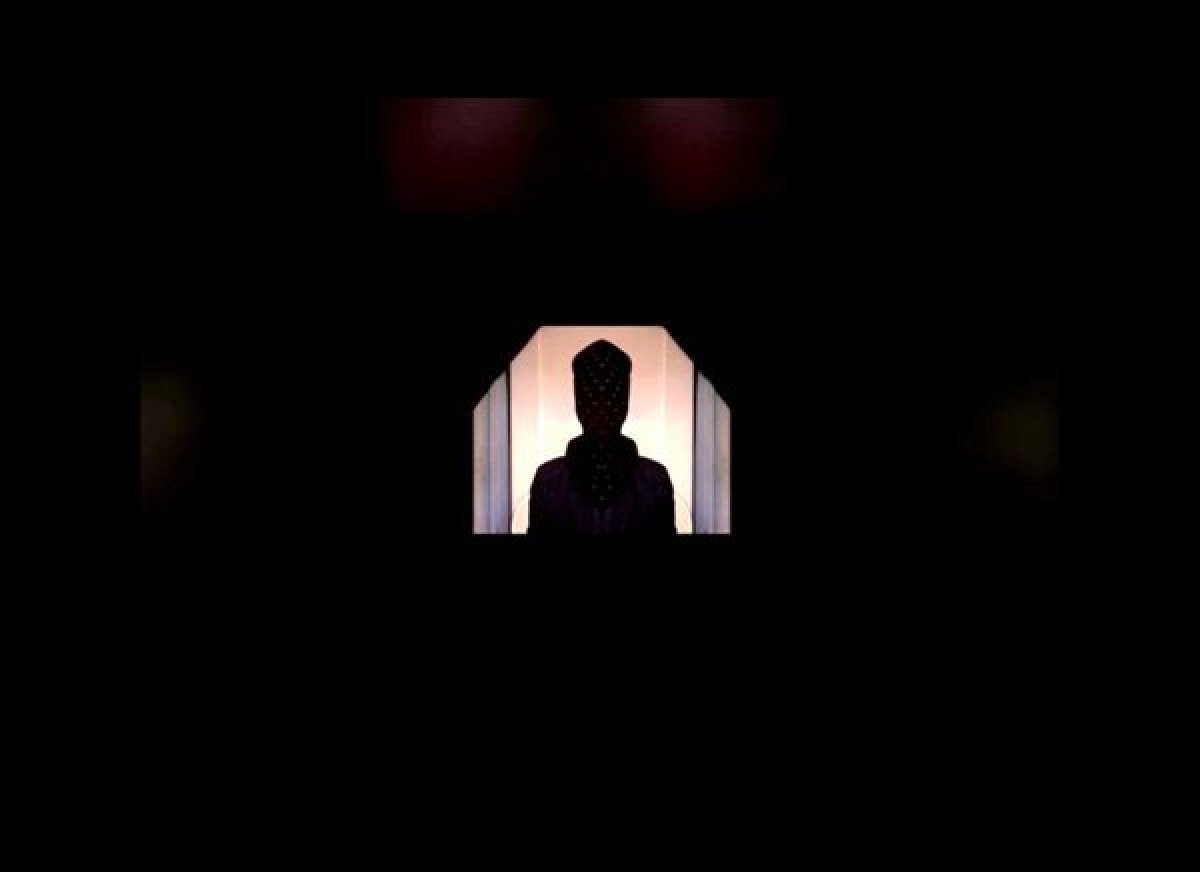

The collaborations were pretty open ended. I was dressing in black and juggling paper cuttings hidden between the two mirror images. Later, I was in a mask and costumes, and swathed in LCD projections. Daniel worked on the video post-production on these, re structuring and mastering the sound.

By the time we did the Sunrise sets, we were immersed in the collaborative process. He was in Sheffield, England, FB messaging and art directing, and I was here in Loisaida (For non-New Yorkers, that’s New York’s Lower East Side), costumed and shining projections on myself. I’d be emailing him clips for his comments. Usually, the sessions would end when he told me “Stop Sending!”

On the black animations, he isolated these ephemeral moves, and paid so much attention to each one! The whole idea of modern art is to capture the ephemeral. More Walter Benjamin, whether you want to hear it or not, haha: “the integrity of an experience that is ephemeral.”

JS: How did your collaboration with Daniel come about? Would it have happened without Facebook? If yes, would the result, the time frame, the reception have been different?

JR: We never would have even met without FB. The process of working together on FB was a breeze. Meeting, becoming acquainted with each other’s work. We had all the lo-tech technology we needed. And a ready venue. It provides a context for how we work, and what we want to say.

We have never met in person, though we do discuss our likes and dislikes about art, and brainstorm ideas for work. Why would we need to meet in person? It’s counter-indicated.

JS: Does your posting of work on Facebook allow you to take your work in directions that it couldn’t or wouldn’t have taken without the ability to instantly disseminate it?

JR: In the collages I am taking the shapes in the other direction, that is, finally making these ephemeral compositions permanent, and then posting them.

It’s not new for me, but new energy has charged up these works, due to this kinetic way of working .

People say on my posts, “Where can I see these?” I say, “You are seeing them.”

Materiality has its value, yet that seems more and more oblique the longer my life in art is immersed in SNS .

JS: Are you going to do anything with these videos?

JR: In 1980, I worked on lo tech vid “Slap Pals.” Julius Koslowski and I threw down acetates onto a TV Screen, and shot animation in Super 8, and transferred to vid. Bruce Tovsky and Robert Raposo composed the music. We showed them at night clubs and the New Museum. Bruce recently told me he remastered those Slap Pals vids. He invited me to screen them in his Brooklyn Navy Yard Screening Room. We decided this would be the perfect time to premier Daniel & my Sunspots Set, and now I can’t wait to show them large screen with great speakers.

JS: What else, with respect to Facebook, are you working on?

JR: I’d really like to see the Sunspots, and maybe some future vids in a 3D installation, using image mapping.

“Sunspots: New Videos by Judy Rifka & Daniel Dibble” will screen at 8pm Saturday, June 22. 106 BLDG 30 is located at Building 30 in the Brooklyn Navy Yard, at Flushing Avenue & Clinton Street, Brooklyn. For more information, visit http://www.skeletonhome.com/bldg30.htm.

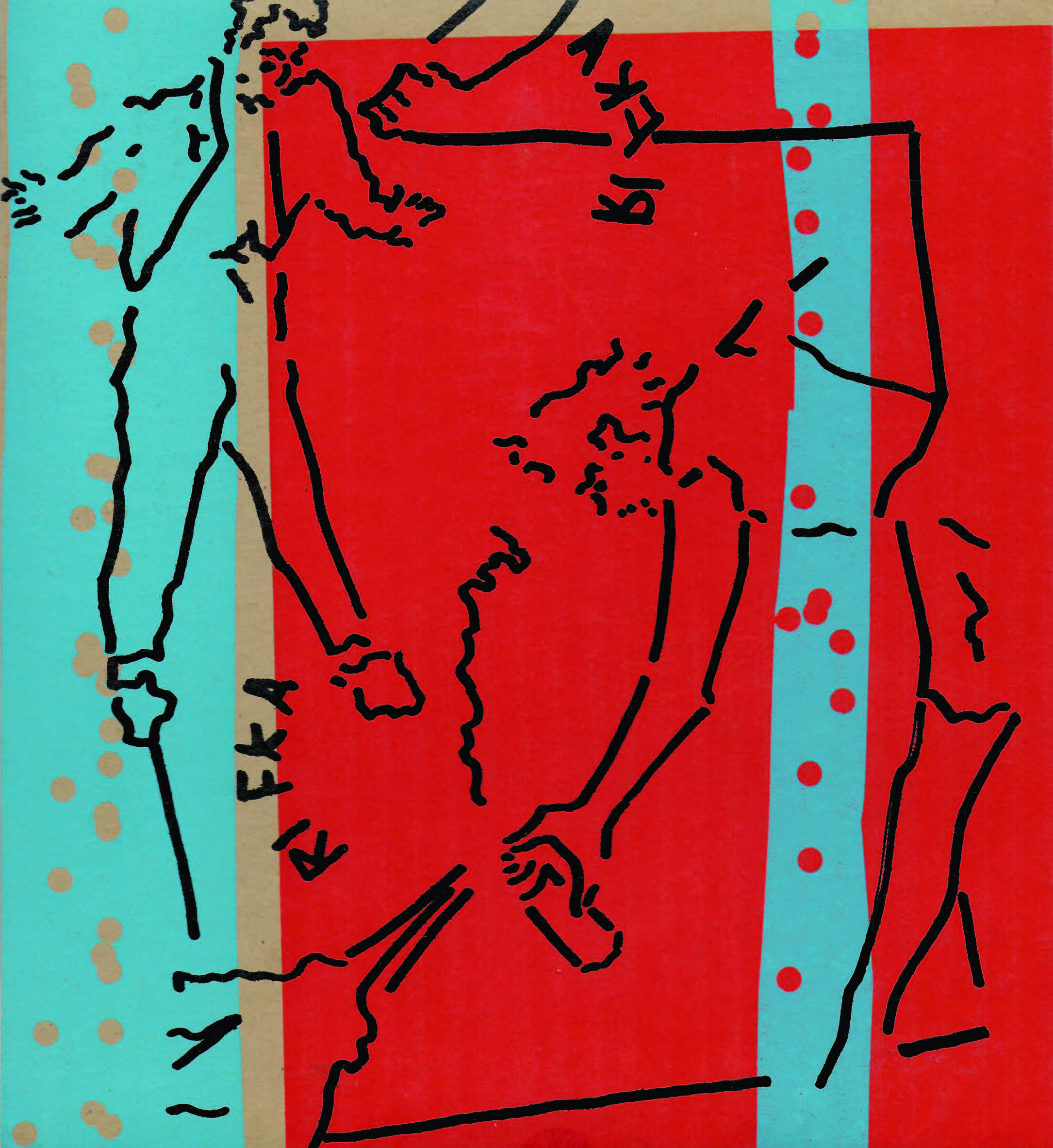

Street Wisdom: Painting From Nowsville by Joseph Masheck /

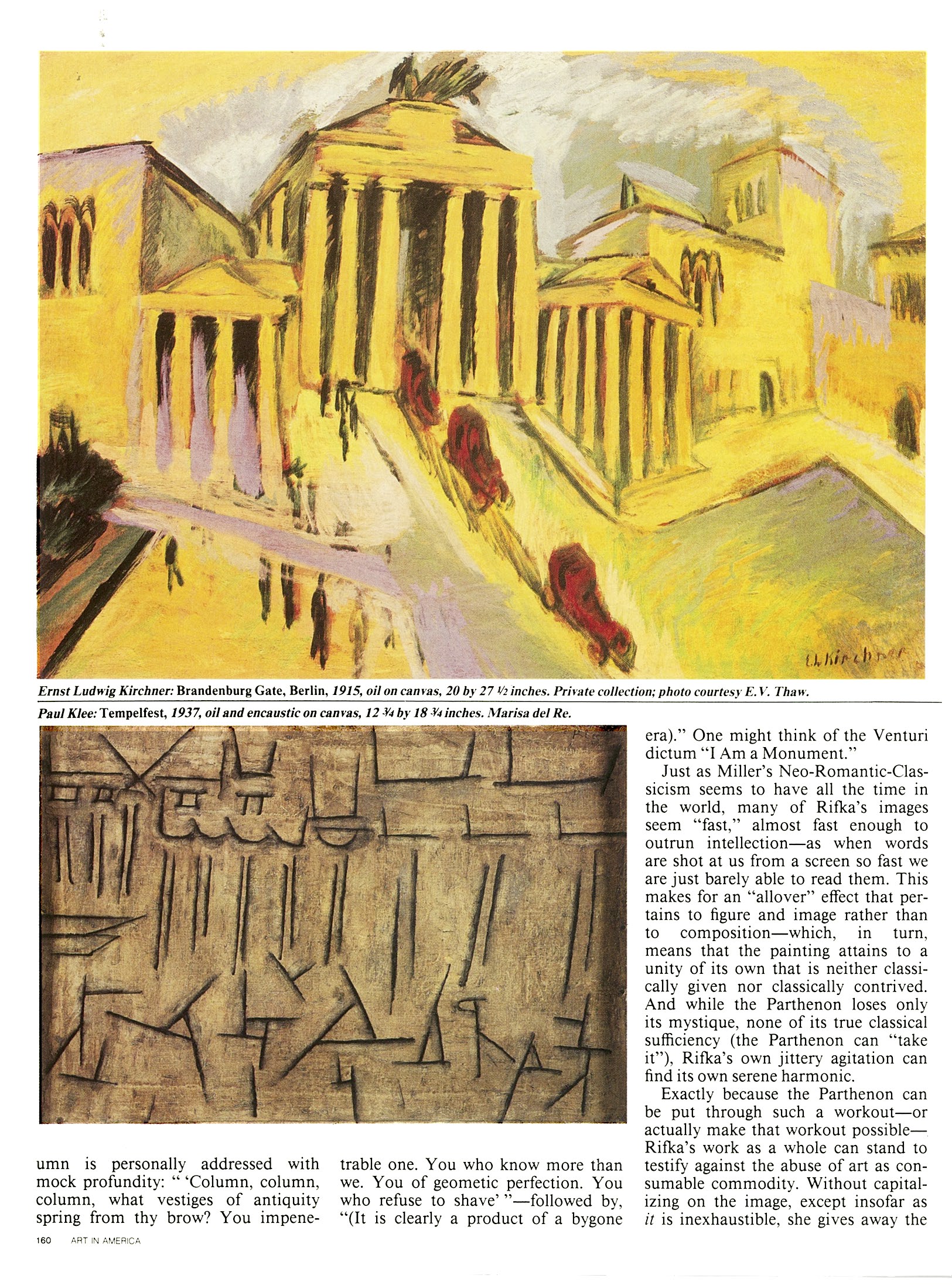

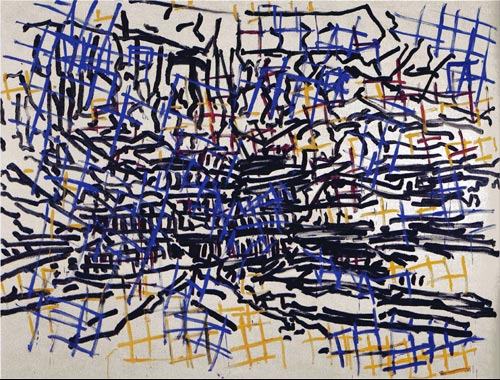

Supposedly, the modern urban consciousness has an atomized character, although those who belabor the fact sometimes betray a desire for reassuring uniformity, with everybody contentedly, domestically alike and all the commuter trains running on time no matter what. To an outlook threatened by the lively and spontaneous, by signs of creative animation and prospects of free growth, nothing could be more different from all our reassuringly clinical, belated Constructivist sculptures sitting mute and sphinxlike in the plazas of antiseptic office buildings than Judy Rifka's utterly agitated paintings. But Rifka's wit, which luckily keeps up with her anxious agitation, entails putting high care into a "careless" look. And in a world charged with contending impersonal forces, this is like advertising in reverse, "pushing" the individual consciousness in all its brave fragility.

"Individualism," per se, has its own limits and its functions, including safely Utopian dreaming. If much is often made of the raucously iconoclastic "Punk" music which drew in young New York painters at the turn of the 1970's, the "high-culture" revival by the Metropolitan Opera of Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill's Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny (1930), in November of 1979 is equally symptomatic of the frustration, but also a certain outsider artworld camaraderie, of the time. Not unlike Brecht's opera, Rifka's truly iconoclastic paintings suggest that Utopias come cheap, which it may be responsible rather than necessarily cynical to face up to. That, after all, idols are for shattering, pertains generally to Rifka's work as I see it, to her single, smaller canvases having one "unscrewed" image on its own as well as to her "big-band" muralistic works, those sweeping cascades, Niagaras to be as hyperbolic as they are of images fragmented and “atomized."

Rifka's is so distinctly an urban art that, in its most characteristic aspect, it may not travel well, except from one downtown to another. For one thing, city culture has had a bad name in America from Puritanism onward, though it has become easier for outsiders to tune in, at least on a level of caricature, thanks to the media. Given the daily experience of an open landscape, true city art must look pinched the opposite, for us in the big town, being the void evoked by all the moaning songs about truck drivers abandoned in trailers by waitresses. Seriously: it is too easy to forget that the weight of European culture, ever since the rise of the medieval market town (of which Los Angeles may be a gigantic survival), has rested on the sheer human density of life in the capital and that this has been by no means unfortunate for cultural life. I notice in the Introduction to the Devout Life (1609) of St. Francis deSales a suggestion for a rather vivid meditation onhell as "a gloomy city burning with sulphur and foul-smelling pitch and filled with people who cannot escape from it." All the more because Francis goes on to evoke as the opposite a landscape vision of heaven's sky in beautiful night and day, it is easy to jump to the false conclusion that he is evoking first the (bad) city and, at that, in terms that anticipate even Frank Lloyd Wright's caustic jibes at New YorkÑ and then the (good) country, whereas he actually assumes that the beautiful sky and light are urban, pertaining to, yes, Jerusalem (I.15f, trans. J. K. Ryan).

Georg Simmel, the philosopher and founder of modem sociology, says much in a lecture on "The Metropolis and Mental Life" (1902-03) that illuminates Rifka's art as fundamentally urban and, here and now, of the New York moment. First comes the itchy unanchored agitation so characteristic, no doubt, of the modem cultural capital itself. Speaking of how the city encourages an intellectual and quantitative, rather than sentimental, consciousness, Simmel holds that "the psychological basis of the metropolitan type of individuality consists in the intensification of nervous stimulation which results from the swift and uninterrupted change of outer and inner stimuli. . . . " It's not merely the pace, but the expenditure of attention and response: "Lasting impressions, impressions which difer only slightly from one another, impressions which take a regular and habitual course and show regular and habitual contrasts all these use up, so to speak, less consciousness than does the rapid crowding of changing image, the sharp discontinuity in the grasp of a single glance, and the unexpectedness of onrushing impressions" (emphasis his). We are accustomed to such an essentially urban consciousness as manifest in the Impressionists' painting of the hustlebustle of nineteenth-century Paris, and even, in a more abstracted way, in relation to Mondrian's "boogie-woogie" vision of New York in the 1940s. What Rifka's jumpy images expose is a still edgier, more anxious and testy, late-twentieth century version of the same mentality.

Where Simmel speculates on the far-reaching chaos that would ensue if all the clocks ol Berlin were stopped for a single hour, I am reminded of a remark made by Edit de Ak, the New York art critic who has done so much to relate the work and world of the real subway "graffiti" artists, and related "Punk". musical culture as well, to the New York artworld. Describing how difficult it is to keep moving on both fronts at once, de Ak commented that the time-consuming "hanging out" entailed by discourse in the one sphere is bound to be shattered by the clock- dominated, business life of the city, so that, after "hanging out" for, maybe, three days with the young outsider artists, she would have to break off contact at an inevitably promising point in order to keep, just late enough to manage, some mainstream appointment. Historically, one might even think of Baudelaire, in the nineteenth century, who, as Walter Benjamin points out, maintained apartments in three different neighborhoods of Paris at once!

Interesting, too, in light of the rootless "float" of Rifka's human figures, which might be taken as acquiescently bobbing around in a gravity-free space, is Simmel's conception of the "blase" attitude that marks the modem city dweller. For in a life structure "of the highest impersonality" what develops is "a highly personal subjectivity" at the heart of the defensive or even aversive urban personality. Today, Simmel's pseudophysiological terms may sound quaint, and amusingly so, yet his thought is nevertheless telling: "The blase attitude results first from the rapidly changing and closely pressed contrasting stimulations of the nerves. From this, the enhance- ment of metropolitan intellectuality, also, seems originally to stem. Therefore, stupid people who are not intellectually alive in the first place usually are not exactly blase." Even hectic, Baudelairean nightlife has its part in this, including even, by extension, ear-splitting rock music nowadays: "A life spent in boundless pursuit of pleasure makes one blase because it agitates the nerves to their strongest reactivity for such a long time that they finally cease to react at all." Battered by otherwise "harmless impressions," the nerves are torn "so brutally hither and thither that their last reserves of strength are spent, and if one remains in the same milieu they have no time to gather new strength." This results, as Simmel sees it, in "an incapacity... to react to new sensations with the appropriate energy," just what "constitutes that blase attitude, which, in fact, every metropolitan child shows when compared with children of quieter and less changeable regions."

(trans. K. H. Wolff in his collection The Sociology of Georg Simmel, 1950). Pop Art, psyched -i; urban if not urbane, brought fast city culture and its "lifestyles" (the term was used by Schopenhauer, not that there was time to notice) to the artistically conscious surface. However, Rifka's fitful shifts of attention from one theme to anotherÑa bunch of these, then a bunch of thoseÑamount not to a passively reflected contemporary dizziness but to a more dogged stalking of the fickle and elusive modem consciousness in its very agitation. More than Andy Warhol, who was content by and large with impassive registration, Rifka goes after and nails down the sprinting temper of the time, bagging it, as it were, not just taking bird-watcher's notes. Because the emotive texture of her work is so honestly, defensively ironic, "streetwise," and because in her judo-like, flexible (instead of flexing) strength there is a feminism so clear as to be transparent (and as such almost unnecessary to remark), she shares something of what must have been the polite sass of the prolific Rosalba Camera, in the eighteenth century, at least in a quip by that painter that strikes me as more Rifkaesque than Warholean: "I am charmed with every thing I do, for eight hours after it is done!" (this as quoted in the once famous "Mrs.," i.e. Anna, Jameson's Sketches of Art, Literature and Character, 1866).

Rifka's work is embraced with delight by the aware young, even if, to put it in New-Yorkese, these kids today don't know from history. Andy Warhol is somebody they encounter in art history classes. Understanding this concerns Judy Rifka's work fundamentally. Far from regressing into a childish realm, safe from fuller consciousness, her painting assumes its historical weight so ably that I imagine it -as downright educational for the kids themselves, whose own dilemmas they might well have thought inarticulable even though, since the Beatles, their fraternity is effectively worldwide. No art that simply mirrored the way things are could be as capable as Judy Rifka's of crossing a definite line of consciousness and then also managing to re-cross it, reporting back from what to most adults might as well be Oz.

Popularly, there is in high-to-late industrial culture a premium on expert invention in the sense of coming up with the workable new trick, with the special gleam of fine art reserved as a consolation prize for moral drabness and conformity. Thus even the grand Victorian phrases, all sort of upholstered in mohair (practical and elegant), with which Carlvie toasts "The Poet as Hero" (in On Heroes, Hero-Worship and the Heroic in History) can begin to sound like the poet or artist as tycoon in a marketplace of things warmingly "spiritual," or even as a mere "star," one who has found a way to "make it" at some mass-marketed "game" that requires its quantum of upbeat "sincerity." Rifka gets into this through her assumed posture of offhandedness, inadvertency, insofar as that appears as an actÑnot phony, either, but an act as such, her “number."

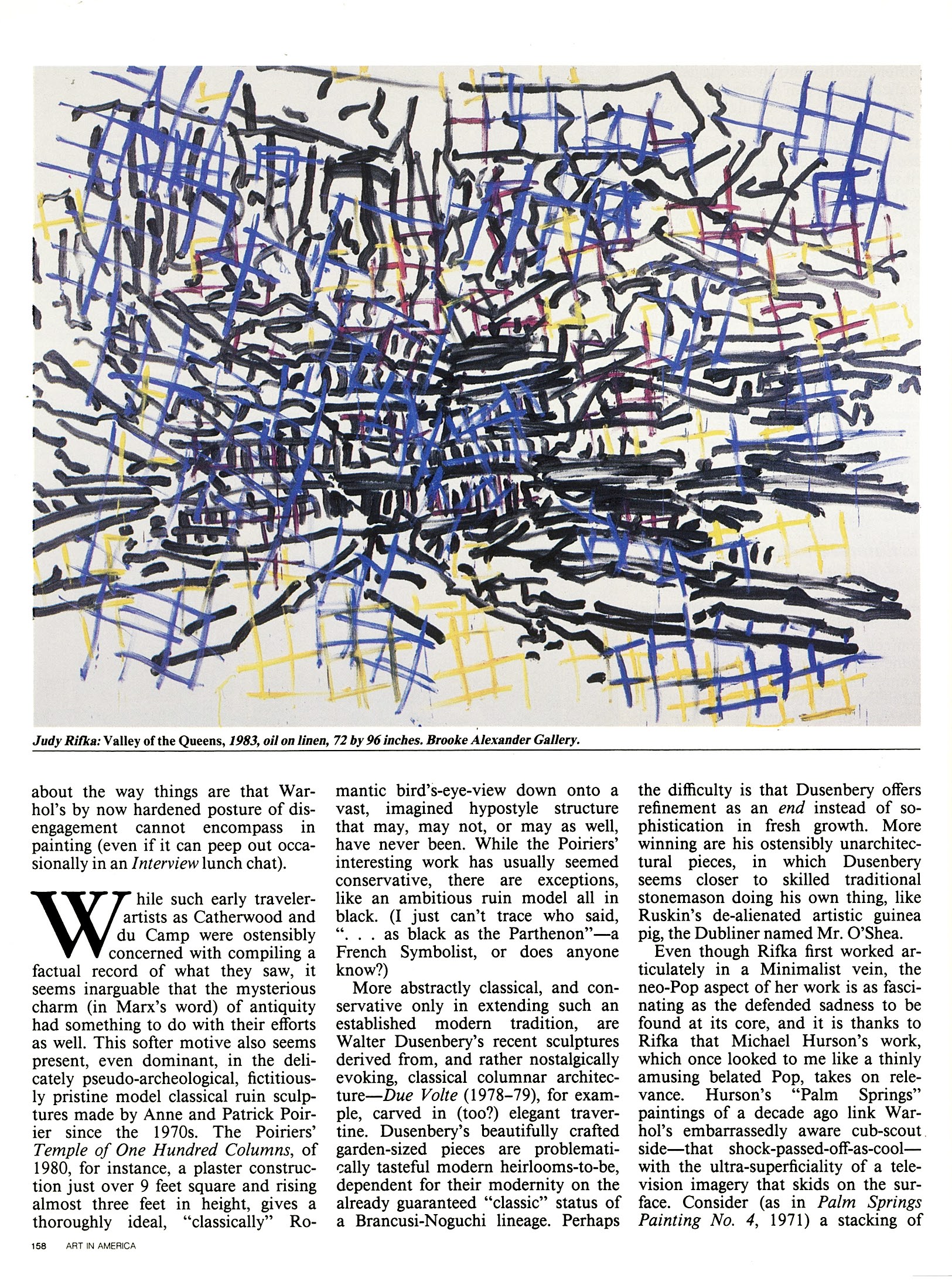

What would it mean to say that Rifka's posture is no pose? At one extreme, that the artist "couldn't help" producing her art as the result of a certain syndrome, helplessly, even pitiably (Arbus); at the other, that the artist was such a dandy as somehow "genuinely" to be all pose, with art as a pseudo-natural by-product (Warhol). The trouble is that both can be "acts" and marketable as such, especially in a populistic American way. For example, the cartoons of Peter Arno are an "act," broadcasting within commoner cultural life, and with a lightness that cannol threaten but can only assuage, a drawing style developed with committed passion in German Expressionism by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and which originally had deep roots in consciousness. Rifka's outright accessibility differs from the populism of an Amo, however, precisely because it encourages a consciousness of superficiality as such, and that is not a superficial thing. Oscar Wilde might have seen this as victory of the critical, over the creative, intelligence; vet there is its ultimate genuineness as art, something more than a theatrical spin-off of pose.

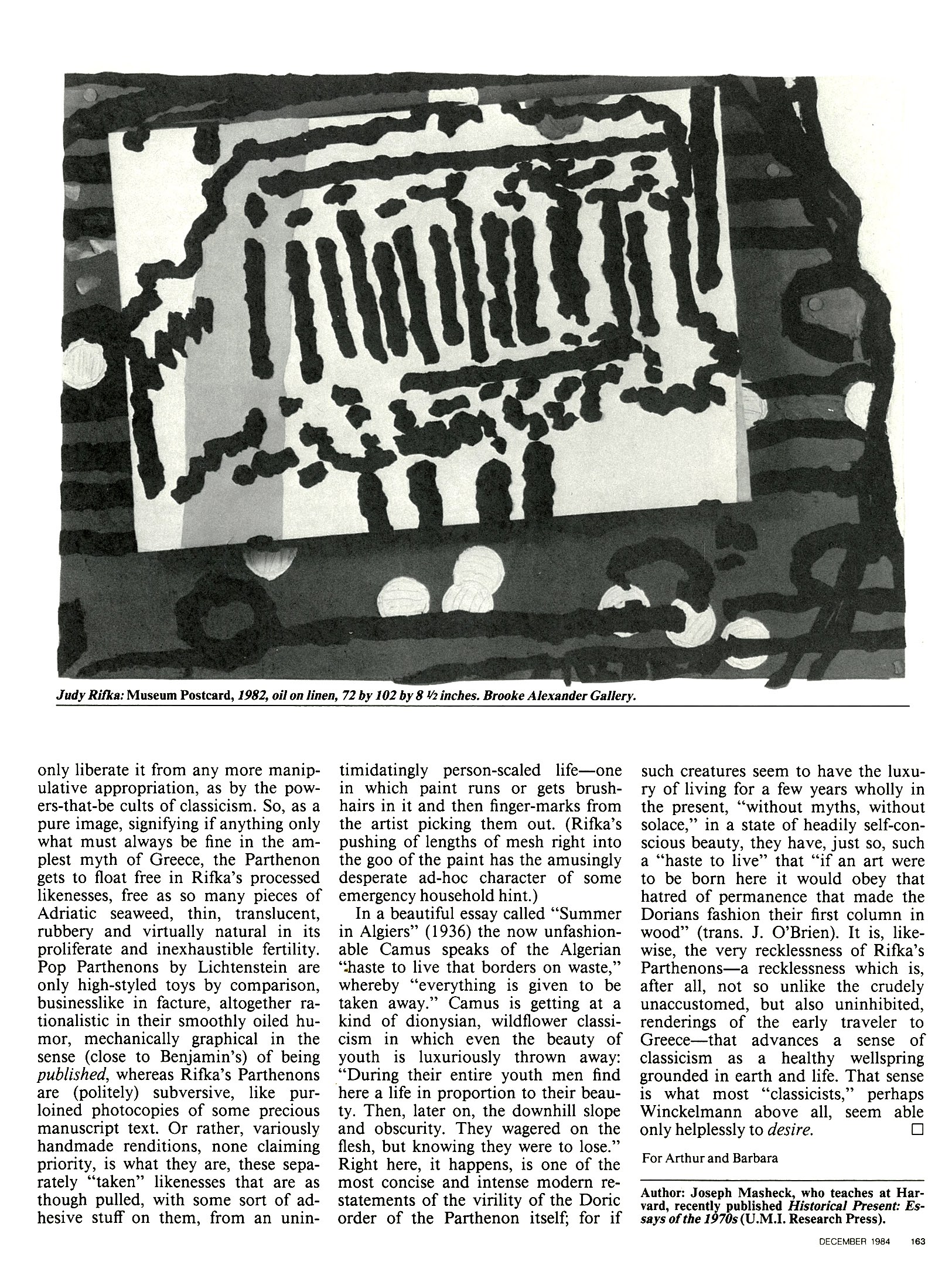

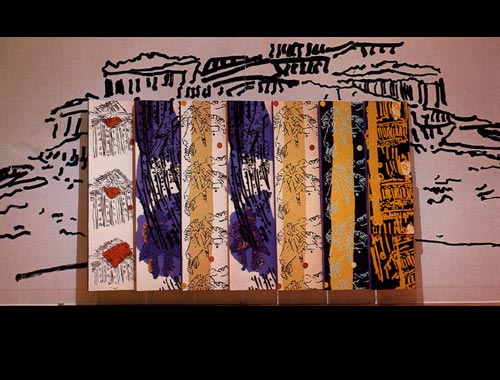

That the leveling, democratic American temper that Wilde himself found bracing here, at least for a few weeks (!), also charmed later European modems, pertains historically to Rifka's art. For one thing, her picture structure sustains a post-Cubist jumble that is, as Theodore Roosevelt might have noted in his famous critique of the 1913 Armory Show, not so unlike that of the "crazy quilt" so symbolically American as well as female and domestic (but also feminine-collective), despite its sources in European folk art. Even Rifka's high-art "appropriations" of the image of the Parthenon, touching base with the European classical tradition at its most hallowed point, are as utterly American as the home-grown "Parthenon" of Nashville, which in the most literal way is sportier, in so much better "shape," than its long infirm European model. Besides, what could be more gutsily wrong-headed than the way the Nashville building (an art museum and hence an unashamed "temple of culture") doesn't mind being parked as it is, like some big '50's sedan, on a flat lot in the world's capital of popular country-and- westem music? Most like Rifka's art must be the sense of doing "it," naive or not, anyway, maybe even doing a whole bunch, as Rifka has actually done with the Parthenon image in her "Museum" paintings. Yet even more important, I should add in a hurry, is the real cosmopolitanism that this art may belie (shucks).

Rifka's painting is altogether in tune with the interest taken by earlier modern European artists in just such American esprit, especially in regard to New York. The cultural importance of New York as the big home town of American art deserves more understanding in a suburbanized Post-War America. It may seem incredible, but when we "war babies" were born, something like 6% of the entire population of this country lived within the City of New York. This city that epitomized urban excitement to everybody from G. K. Chesterton—who said the neon signs of Times Square would look wonderful if one couldn't read English (my chauvinistic grandfather included these in his periodic tours, but tried to drive by fast enough so that we kids couldn't read them)—to Mondrian—who took up boogie-woogie —was a floating congress for everybody with ideas and, well, gumption. Bostonians may have said crude ambition, jealously enough, after the pubishing industry moved to New York in the nineteenth century; yet there is a beautiful early photograph by Steiglitz of Manhattan, with the smokestacks of buildings and ships steaming away, just arrogantly-enough entitled City of Ambition.

Stuart Davis's New York to Paris, No. 1, painted in 1931 (University of Iowa, Museum of Art), has transatlantic cultural contact with the jivey Paris of Leger as its overt theme. In a hurry and jumble that anticipate Rifka, Davis intertwines a fishing boat with nets, a New York "el," a cliche-Parisian cafe, telegraph pole and wire, the Chrysler Building and a luggage tag hanging down into the cheerfully reckless "composition." This whole cluster of emblematic items is dominated by a big, sassy, silhouetted, American-in-Paris "gain," to recall a popular term of the time of World War II, strutting by in stocking and high-heeled shoe. In the next decade, the war itself displaced major artists, among them Duchamp and important Surrealists but also Mondrian, to New York, where, within a few years, American painting would for the first time challenge and even exceed the centuries-old artistic claims of Europe. Already here, however, in 1931, with Stuart Davis being so American even in "grooving on" Paris, is an intimation of Rifka's rather more anxious and fretful urban jitterbugging. Not that everything is quite that simple or causal: in a subtler way in Rifka's work of only a few years ago, even the Abstract Expressionism of the booming postwar years reverberates, notably in a kind of twirling drawing-in-paint apparent in, especially, latterday works by de Kooning. Yet, without being deterministic, Davis's painting does offer one way "into" Rifka's altogether "nowsville" art.

The various multiple images that flit so seemingly irresponsibly, or with anesthetized disengagement, across so many of Rifka's canvases, come from a "stock" of sorts. They are so distilled, in the processes of being drawn on transparent acetate sheets and then jiggled around in opaque projection for placement as forms in the painting, and too digested, as such, to amount to simple "appropriations." What they do have in common with an esthetic of "appropriation" prevalent todav is their air of being initially "pulled down," rather than elevated, in the hierarchy of images: unlike the high-culture appropriation of primitive and folk arts, early in the century, many an imagery of mass distribution is now borrowed from the technical realms of the media, including television (we hear much of this) but also the visual parlance of slickly calculated advertising. Such is a broadcast imagery in the root sense, one scattered far and wide. Appropriating becomes an issue of qualifying the sometimes almost magically authoritarian character of images as coming from on high, that is, from the same high stratum, ironically enough, in which works of fine art stand as special tokens of cultural ultimacy.

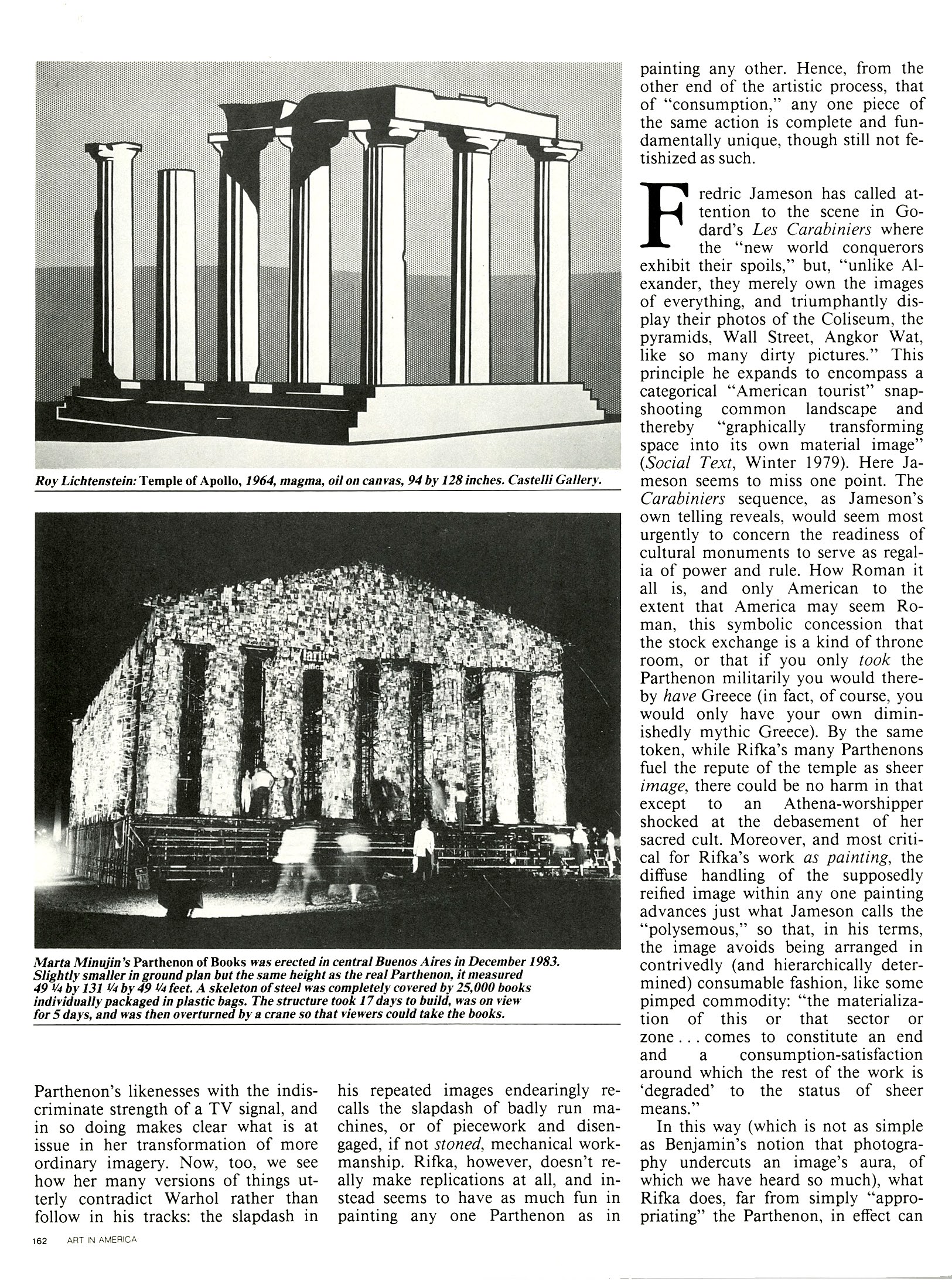

In a way, this advances a lactic first pursued less critically by the Pop artists of twenty years ago, as when Roy Lichtenstein took over comic-book imagery and transformed it "abstractly" into high art. And now that appropriation has a sharper critical thrust, Henri Zerner's discussion of Lichtenstein's Bobby Kennedy cover from Time magazine (in the catalogue of an exhibition on The Graphic Art of Roy Lichtenstein in the Fogg Art Museum, at Harvard University, in 1975) seems keen: Zerner points out that the Time cover, for which, significantly, Lichtenstein made the color separations himself, is, even though it constitutes an edition in the millions, "more of an original print than so many Braque or Chagall lithographs that are merely gouaches skillfully reproduced by professionals and signed by llic master. Now one might think, further, of Rifka's generative use of drawings on transparent acetate sheets in analogy with the reproductive transparencies of Lichtenstein's color separations, in which sense she makes "monoprints," of a sort, from her own "stock." Picture Rifka juggling her acetates to the beat of rock music and you have some idea of her approach as extending Leger's with-itness and even Stuart Davis' and Mondrian's flying in the very face of the European disrepute of jazz as (overstimulating) "low" What is easily forgotten here, given the popular sense that in history things merely happen, like the weather, is precisely that texture of conviction where in if nothing went against the grain enough to grate, something must be wrong. This has generally to do with modem culture as critical, even adversary, culture: complete inoffensiveness probably signals im- potence. Nevertheless, not even all the partisans of modernity have had an easy time with the jazz esthetic. In an essay called "Plus de Jazz" (1921), collected in his Since Cezanne, the distinguished art critic Clive Bell considers jazz childishly anti-intellectual and beneath the dignity of high culture; wittily enough. Bell dismisses the prose stvie of Virginia Wuolf as insufficiently "avroche" (raga- muffin) to offer a literary parallel to jazz syncopation and discontinuity. At the end of the same decade, a brief notice by George Bataille entitled, in English, "Black Birds," treating "Lew Leslie's Black Birds" at the Moulin Rouge in 1929, goes right for jazz as primitive and a decadent satisfaction, which would hardly have encouraged taste-minded skeptics. Later, in the very time of Pop Art, Theodor Adomo, dating jazz's European impact to about 1914, would lash out at the whole mode in an essay, "Perennial Fashion— Jazz" (in his Prisms, 1967), where jazz is found pseudo-natural, pseudo-vital and full of cliches and conventionalized variations anyway, not to mention its being psychologically regressive along sadomasochistic lines! If in extending a new "jive" in painting now, Judy Rifka might run into some of the same flak, she would at least be in good historical company. The way Rifka will do whole lots of one thing and then of another, piles as it were of each, sometimes interchangeably, is itself like the reiterative culture of phonograph records playing over and over again. It's tunny how a piece of music on a record gets taken to heart: the record wears down, however imperceptibly with each successive play, becoming ever less illusionistically real and ever more obviously recorded, objectively speaking; meanwhile, as the music in all its nuances is however gradually effaced from the record, it can in a sense be said at the same time to be inscribed more and more vividly in memory, not too differently from the way Rifka's images partake of the schematic concision. In either case, the unaccustomed spectator may be stumped by apparent abbreviation, whereas a buildup of familiarity tends to help in the negotiation of complexity— as I can still remember from first learning to hear not only the music of Bach, but then, also, more broadly, the "motor rhythm" of rock-n-roll.

Artistic richness turns out to be more important than where something ranks on the totem pole of culture. Besides, it becomes difficult to tell in modern culture what "high" or "low" origin is, as musicologists found out when they wondered whether "Annie Laurie" was a folk song or a song composed in folk manner by a sophisticated person; Donald Francis Tovev affirmed the latter, claiming in an essay on "Normality and Freedom in Music" (1936; collected in his The Main Stream of Music} that "its first seven notes are obviously the work of a lady or gentleman picking out sweet appoggiaturas on the pianoforte." What gives "Annie Laurie" away, it seems, is its reliance on standard harmony, much as the classic subway "graffiti" art of the turn of the late sixties through the 1970's related to the preprocessed graphics of certain more hard nosed, "post-naive" comic books. It could be maintained that "graffiti-type" art inevitably achieves a special "lowbrow" status within sophisticated highbrow culture just because it is so pre-tailored to a special, limited satisfaction, much as, say, the winning songs in the middlebrow "Eurovision Song Contest" tend to fall back on nonsense tra-la-las that will sound catchily "cute" in any language. Only an art as sophisticatedly rooted as Rifka's is prepared to transcend limitations of this kind. What is at stake with "graffiti" art is a complex affair, but Rifka's work does raise the issue. Precisely as painting (and thus as deeply linked with our earliest life experiences of control over messmaking), such an artwork constitutes an unconventional and clearly potentially threatening outburst of individuality in the public context, one that any authority would prefer to control, not to mention hoipolloi for whom the very prospect of freedom is a threat.

Furthermore, the literary culture is always unwilling to see such artwork, whatever its virtues, on its own terms as visual art. This is complicated bs the technical terms "writer" and "writing" for the graffiti artist and his macho artwork (only one female muralist of the subway cars seems to be mentioned). It is more helpful when these terms are reserved for younger aspirants starting out with the justifiably offensive and much more textual, unpictorial "writing" applied to the insides of subway cars, the problem being that the same terms are also used more broadly to include the nowadays ever rarer, extravagantly visual exterior murals. Curiously enough, in Dominican monasteries of Savonarola's day, the manuscript artists were called not "miniatori," or miniaturists, but "belli scrittori," or "fine writers" (R. M. Steinberg, Fra Cirolamo Savonarola: Florentine Art and Renaissance Historiography, 1977). Generally relevant, too, is surely the literary bias that American culture probably inherits from the British Isles. In the first mainstream study of subway graffiti art, the novelist Norman Mailer's The Faith of Graffiti (1974), a glossy picture book with art-historical pretensions, Mervyn Kurlansky and Jon Naar's color photographs show not a single large, coherent, exterior car mural. There is, beyond, a historical problematic as well. Since practically all organized attempts to "beautify" or "enliven" the city with outdoor murals result semiautomatically in innocuous art, it is worth considering that such public works recall the Utopian attempt of modern artists under the Weimar Republic to apply "bright paint... to the facades of pettybourgeois houses in German provincial towns, to hide the shame of their structural disgrace and the emptiness of their eclectic ornamentation" (this according to Hellmut Lehnmann-Haupt, Art Under a Dictatorship, 1954).

These considerations may seem to ramble, but only, perhaps, in a way like that by which Rifka's painting sustains relentless transformation. For her, one thing leads on to another in a fertile stream of ideas that seems tinged, knowingly enough, by the anxious, "hyper" urgency of life on the run. Yes, in a general way this has to do with the Joycean streamofconsciousness (and in Ireland too, by the way, as no doubt even in the smallest nation, slower folks affect to disdain the fast pace of the cultural capital). Let it not seem, however, that this indicates a stream of ideas in any verbal sense, of thoughts first presenting themselves in programmatic form, except insofar as James Joyce himself, as Vladimir Nabokov insisted, w?.s concerned with an essentially visual stream of ''images." This is important because it rules out any bracketing of Rifka's work within the special but inevitably inferior category of illustration, even illustration that can be patted on the head for special astuteness, as when Baudelaire does just that for Constantin Guys in the famous essay called "The Painter of Modem Life" (1863). No, understanding that this painter's selfconsciously stylish, "with-it" work is not "literary," and pertains, if anything, to a musical, rather than verbal, culture, makes it possible to see how, as painting, it is, perhaps most ironically of all, also visually abstract. No wonder why, to the extent that they are "motifs" at all, Rifka's images come and go in packs, like "extras" having few or no "lines" whose role is simply to advance a general hubbub.

The set of twelve somewhat "graffiti-like" gold panels called Surface Tension, from 1981, is telling. Here is a figure that has to be the artist, however generalized it also is, struggling with a stretched canvas, which is to say, with "art" and, at that, with the capacity of representation to show the very struggle of art. The gold is thinly and "sloppily" smeared, in a way capable of alluding to a certain kind of gustatory abstract painting a decade ago but that also advances, now, a post-Pop sense of deliberately superficial mockluxury like certain lowbrow home furnishings. At the same time, the irony that such paintings themselves are capable of becoming tokens of luxury, far from seeming inadvertent or accidental, might as well be a comment on the built-in reflexiveness, by itself so tiresome, of all painting content to be "about" only painting. Most typical, looking way back three whole years, is the slight female figure contending, with a witty clumsiness, against the awkwardly physical resistance of a supposedly mainly mental kind of work.

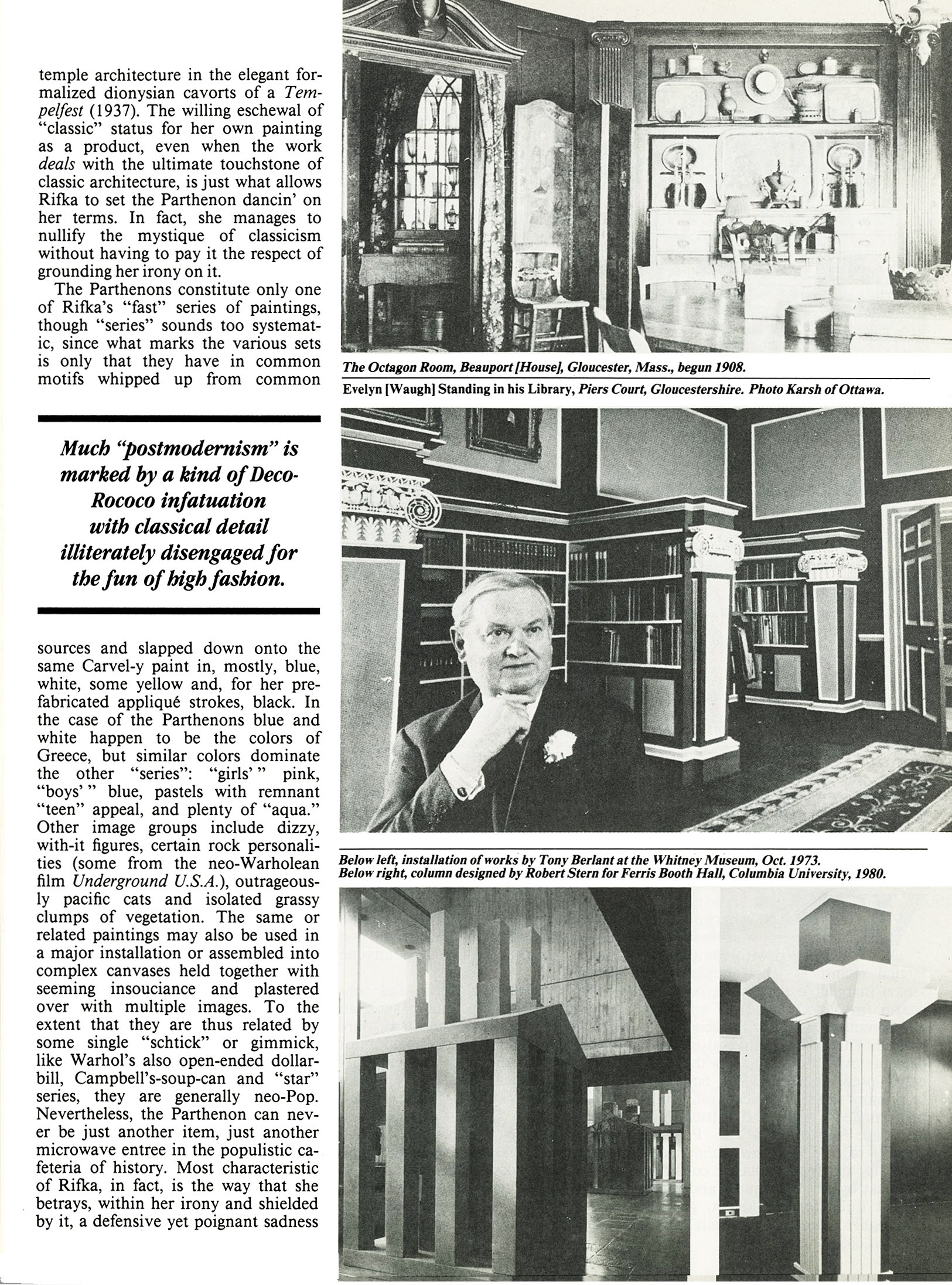

Doubts may come and go about the facile effect versus the studied facility of the means advancing it. With Dracula's Mirror, 1982, it is at least as funny as it is esthetically serious to see the stand-in, representational aspect of painting, by reference to the "mirror" of reality, put on rolling casters, like a (Duchampian?) suitcase full of "pure thought" equipped with wheels. As the esthetical trapeze artist in jEso si Que es!, also of 1982, might understand, Rifka's large Valley of the Queens, of last year, can charm one even by the ironically delicate glitzy dazzle of light bouncing off the rabbit-skin glue with which the linen is primed. But doubt can only return once it has departed, and if there may well be a temptation to make a facility seem profound art as offering an easy time that can only keep happening because the "heavy" is in fact made to seem light. Wittgenstein said that a whole philosophy could be written in the form of a joke book.

If you had only raw physical data on Rifka's hefty paintings, such as the facts on their materials, size and weight, you might suppose that they made a con- structivist point about displaying the concrete materi- als and single-minded pragmatic of the engineer's version of the "real world"; yet to know them in the flesh is to understand how funny that misconstrual would be. To slam the elements of a painting together as Rifka does also happens, typically enough for this sophisticated artist, to involve the history of painting since Cubism. Rifka's work does extend Cubist concreteness as that passed into a less complex, less metaphorical materiality in Constructivism as tending to make everything, from paintings to chairs, over into sculpture, once wood equals wood, metal equals metal, and paint is only pigment. Once paint is nothing but paint, however, we know that painting's own poetry, just what we were after, has slipped through our fingers. In this sense, what Rifka really elaborates is the potential for an ironic concreteness: painting fighting back against gross matter. Her art has strata of irony, including historical sophistication, as well as a (sometimes preposterous!) mechanics of parts adding up to wholes. It displays a brasstacks shop-talk even as it opens the possibility of estheticism while, from a slightly different angle, by its very iconoclasm, it shows that estheticism is not necessarily escapist.

In an impressive installation, early this year, titled, Why die, at the 51X Gallery, one of the new "young" outfits on the Lower East Side, Rifka put together a melange of wall-drawing, painted drapery (even on the ceiling) and images on canvas, the whole comprising a comment on militarism and looming holocaust that was all the more powerful for not simply collapsing art into a journalistic gesture. On balance, the project was a Goya-esque outburst of beauty as much as of rage, ultimately "fine" in managing to articulate frustration itself (no mere irony, that). Inevitably, the "Mercenaries" series of Leon Golub was recalled; yet I am also struck by the fact that Golub's big, unstretched images, especially of man-toman cruelty as embedded in sanguine fields of red, in turn relate to the abstract Philip Guston of The Tormentors, 1947-48 (San Francisco Museum of Art) and to the large tradition of such protest within "pure" painting in which loom Robert Motherwell's "Elegies to the Spanish Republic" (and later Irish equivalents), themselves abstract progeny of Picasso's Guernica. Significantly, in light of Baudelaire's fascination in the "Modern Life" essay with military nonchalance, Rifka's individual paintings of soldiers keep urgent the matter of macho swagger in relation to cruelty and violence, while in more ostensibly esthetic terms, their brown-and-green "fatigue" palette even recalls the direct involvement of Parisian Cubists in the development of camouflage during World War I. Rifka's installation was not immune to the problem of what might be called hot-headed pacificism, but its sheer gusto, as William Morris, Brecht and perhaps some Dionysiac musicians of our day would have been pleased to see, showed that an art of peace is not condemned to wear a dreary face.

That Rifka is prepared to deal with themes along the lines of nuclear holocaust as well as the dizzy, nerve end excitement and delight of rock music and dance says something about her moral range that tends to get lost once an artist becomes typecast with more or less trademarked images in the processes of cultural distribution and consumption. Factors that operate on the receiving end seem to include an understandable human preference for whatever strikes home as against whatever may be challengingly alien; a desire to have things simpler than they are, if only by avoidance of contradiction; and a quasi-pornographic fascination with the "bad" as titillating from a safe distance. I say this because if the 51X installation was Goyaesque, Judy Rifka is more generally Hog- arthean. Consider, in general, the "Rake's Progress" aspect of her painting, but also, in particular, the case of a famous Hogarth print. Hogarth's Gin Lane is actually one half of a didactic pair, its pendant being another engraving called Beer Street: everyone recognizes Gin Lane, with its spectacle of individual and social degeneracy through heavy drink, while only specialists seem even to know of Beer Street, with its contrasting display of a mellower life of kinder social relations. At least for the time being, Rifka might have to endure an opposite receptivity, an automatic preference on the part of spectators for her cheerful, "Beer Street" paintings, if only because "Gin Lane" may strike too uncomfortably close to home. Nevertheless, what deserves not to be lost sight of in the meantime is her exemplary ability to handle evil without being stung by it, which is the moral aspect of an artistic range that by itself might have seemed merely dizzy and all-over-the-place, instead of sweeping, as comprehensive as Hogarth's distinctly sensible and middle-class "take" on eighteenth century London.

As I write, a certain popular song of the moment, German in origin, captures something of the spirit of Rifka at 51X, but by means of a radical sentimentality that calls up the utter freeze of childhood terror. The song, "99 Luftballoons" (translated as "99 Red Balloons"), by "Nena," is about the sudden, sweeping horror of thermonuclear war, for which a certain mentality has, with shockingly childish unreality, pseudo-rationally prepared itself; important to its effect is Nena's blase bounce and cynically "innocent" lilt. This seems relevant to Rifka's contrivedly "childish," pasted-together, whistlingly preoccupied approach, even when her absorption does not spill out naughtily onto the wall. For her work is more than uncritically infantilistic and critically transitory thanks to its calculatedly raw, "adult" edge (this seems distinctly American in comparison with the taint of bitterness in the German song). It is as though, just as when Pandora opened the famous box everything escaped but hope, it might somehow, someday, be possible to look back on our present condition as "dated" because of its having been overcome. That said, what is most adult is -again the raw edge - that we need to be reminded that wishing will not so.

What an uphill battle it seems nowadays to make spiritual ends meet! How helpful, in the circumstances, to have an art that may look superficial, or at least "forward," in its dizzy recklessness but that will not let us off lightly. Such has to do, I think, with nothing less than the redemptive power of art. There is no turning back from consciousness sentimental art is bad only because life is short and death awaits. And once we are sentiently conscious only yet more sentient consciousness will do.

Bykert Gallery by Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe. ArtForum, April 1974. /

Judy Rifka's paintings dominated the show. I've left her work until last because it has some - vague but insistent - affinities with that of Gerald Horn and Joshua Neustein, to whom I shall come in a moment. Rifka's work is done on cardboard, which provides a soft, brown field for an image made out of one or two colors.

This image is the result of a procedure that begins as a way of getting from one mark to another, across the surface of the piece, and ends with the creation of a kind of envelope made out of layers of paint. the black shape, which was initiated by tiny squares and rectangles - displaced intuitively and then connected - began and ended the paining process. The white shape, introduced after the black configuration was more or less established, is literally sandwiched - painted in and then mostly painted out - by the black, and this is also how one visually experiences the work. Rifka has put her finger on a neglected but ostensive feature of painting's conventionality, which is that opticality may be as much a consequence of conventionality, which is that opticality may be as much a consequence of physical actuality as of - for example - chromatic interaction. In this, she addresses the question most crucial to painting in general at the present time: the question as to how far the - currently compromised= abstract "depth" of pictorial space can be newly considered- retrieved - through attention to the material basis of the conventions on which that experience of "depth" relies. Rifka's paintings are flatter than almost any other work that comes to mind, including that of others- Robert Ryman, for example - who are concerned with the material qualification of the painted object. At the same time they suggest a space infinitely deep, and its the scope of this evocation and accommodation of paradox - of a subjectively considered material dialectic - which leads me to say that Rifka's is the most devastatingly original formulation of painting's identity that I've encountered in some time. I need hardly add that this effect is immeasurably enhanced by her use of materials which are uncommon in painting and familiar in the everyday world.

Judy Rifka at the Chocolate Factory by Lilly Wei. Art in America, May 2008. /

Judy Rifka's recent exhibition at the Chocolate Factory in Long Island City was her first solo show in the metropolitan area in over 6 years, and one wonders why this talented, volatile artist, associated with the artists' collective Colab and the freewheeling East Village/Lower East Side scene in the late '70s and 80's, has absented herself for so long. The show was titled "Nostos," which is apparently the ancient Greek root from which the word "nostalgia" is derived and means a return or homecoming as well as a species of fish - all of which is appropriate to Rifka's current project.

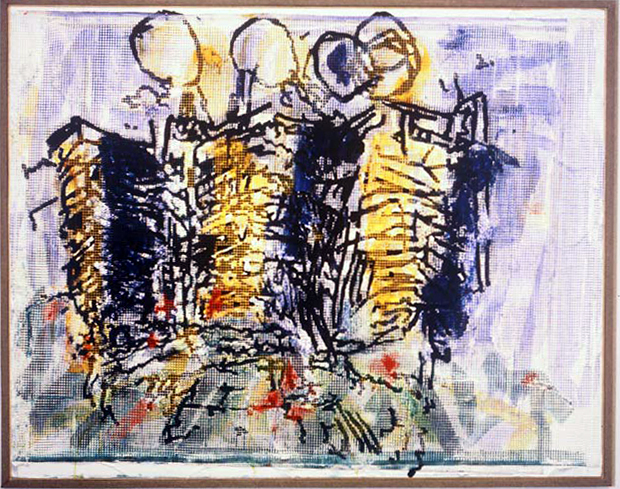

Entering the basement gallery, reminiscent of the unfinished-looking, no-frills exhibition spaces of 30 years ago, you first encountered 14 paintings in the round, as Rifka calls them - propped at intervals against one long wall, with one in the elevator shaft. These works conjure up earlier forms of life - or perhaps future ones - in muted colors threaded with flashes of brighter hues, as if their brilliance had been eroded by salt, sea, sun and time. These fantastical forms, or "Totems," are about 6 feet high, their contours crenellated, spiny and suggestive of snarling dragon heads, sea horses and various mythological creatures reduced to skeletons, a return to some more recalcitrant, primordial state. Rifka shaped these painting/sculpture hybrids - half-abstraction, half representation - by stretching their linen supports tightly over an armature. The apparently casual brushwork - a gestural patterning of blues and greens, with some white, some red, against the neutral tan of the support - is set in opposition to the more decisive-seeming intricacy of the structure.

Scattered on the floor before these works were globe like shapes the size of beach balls, similarly painted but more regular in configuration - as if they were rocks, perhaps, rounded by the sea. At once organic and inorganic in aspect, these objects seemed to be a kind of ecological fallout, artifacts washed ashore. They read as reliquaries of a sort, but whether they had been abandoned or salvaged, it was hard to say. Mounted on the opposite wall were paintings, modest in size, also oil on linen, whose swirled shapes - in vivid, radioactive reds, violets, corrosive greens and blues - had all been laid down with Rifka's characteristic verve. They were also collaged with circular and less regular sections cut from other paintings, then affixed to the linen, along with two or more shapes placed symmetrically, even heraldically, in the field. The layering recapitulated the idea of three-dimensionality embodied in the painting/sculpture hybrids, but the effect was much closer to relief.

Tightly orchestrated yet surprisingly expansive, the installation also resembled a grotto - one populated with sea-changed, curiously beautiful grotesquerie. Rifka, whose highly charged, cross-disciplinary way with painting is still evident, even if it is here brought to bear on something more like sculpture, is clearly an artist ripe for reassessment.

Rene Ricard's Letter to Judy Rifka /

New York City, 1981

History of Sculpture by John Sturman, Art News, January 1989 /

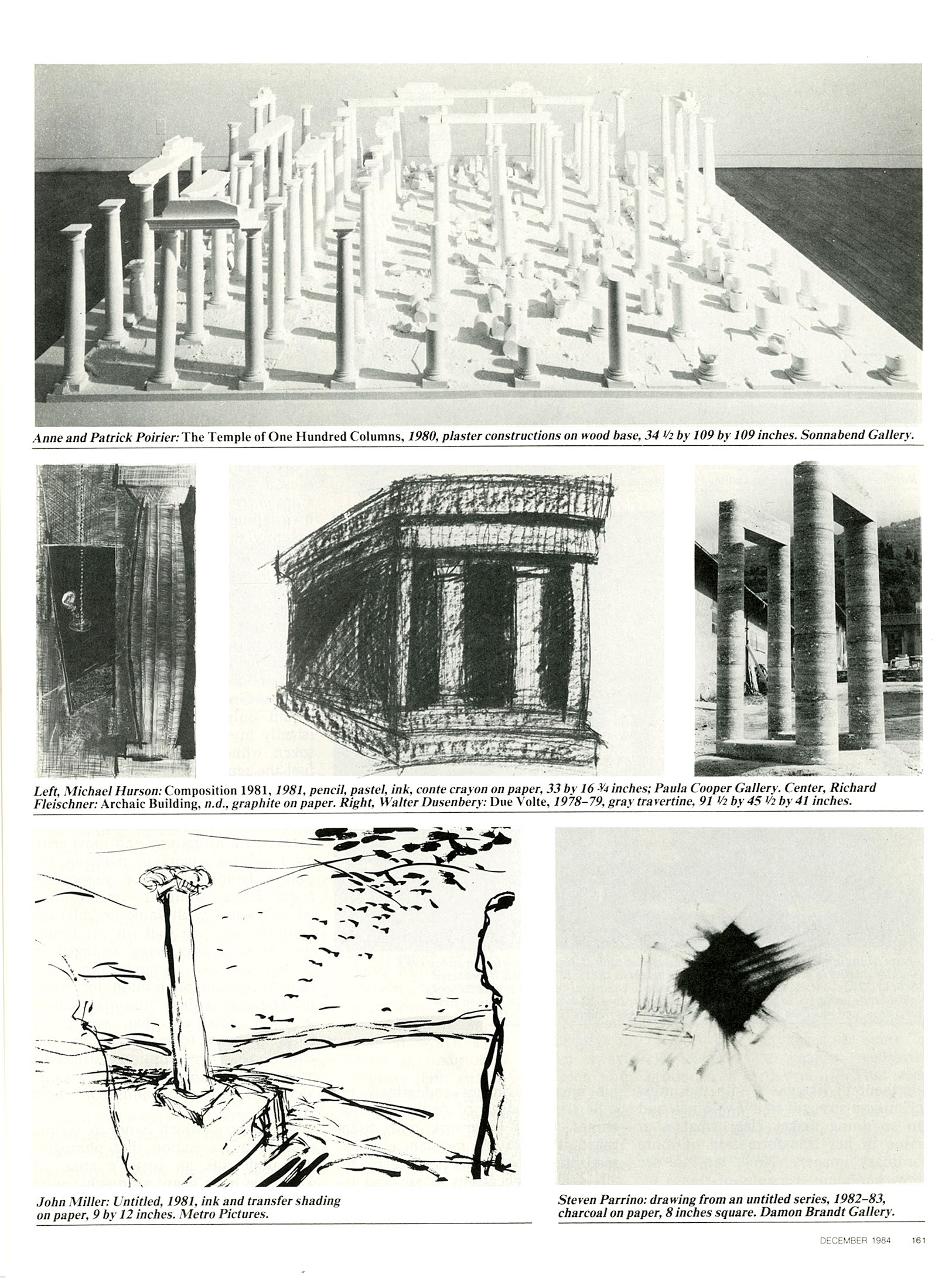

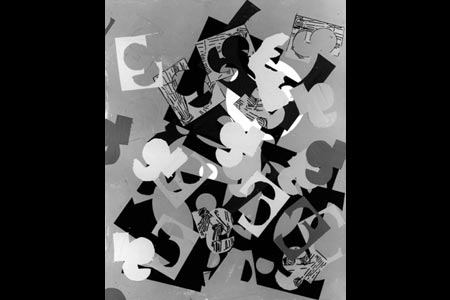

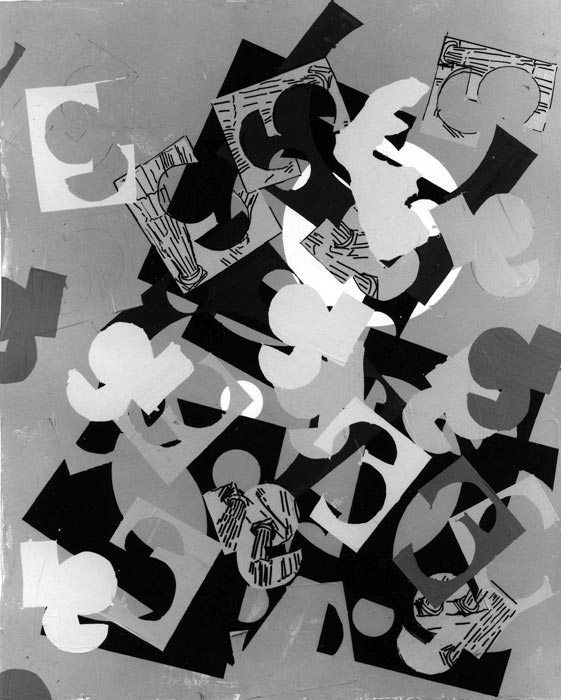

The 13 paintings in this show belong to Judy Rifka's "History of Sculpture" series, and they blend many polar opposites past and present, classicism and modernism, figure and ground, abstraction and representation, great art and commercial illustration in an unusual, provocative manner. While the titles Acroterium, Athena Nike, Victory at Samothrace reflect their classical inspiration, the canvases resonate with echoes of Constructivism and the street- smart sensibilities of the East Village. Rifka fuses these far-flung influences to create a bold style all her own.

Particularly striking here is Rifka's palette, which consists solely of black, white, and gray, with an occasional muted taupe or tan. Although the avoidance of color may seem somewhat obsessive, it has the unquestionable advantage of directing the viewer's attention to the content of the work. Applying many thin layers of acrylic paint to simulate a densely collaged effect, Rifka relies heavily on visually recurring elements geometric shapes, the templates from which these forms appear to have been cut, profiles of Greek goddesses, and what look like hastily drawn Magic-Marker sketches of classical architecture and sculpture. These motifs give the paintings a strong sense of unity and coherence both individually and as a series.

There is also a satisfying alliance of subject matter and technique the complex layers of paint neatly parallel the almost archeological way in which classical elements turn up amid the abstract forms. In Laborde Head, for example, a goddess in profile lies among the geometric forms and cutout templates. In Fragments of Nike, a similar head seems to have been cut out of a white square, which is superimposed over a profusion of other shapes. It is almost as if Rifka has strewn the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle across these canvases. With their mixture of the classical and the modem, these are perfect postmodern puzzles for the viewer to put together.

The Chocolate Factory by Cassandra Neyenesch, Brooklyn Rail, October 2007 /

"Rifka's Work Seems At All Times To Change By Leaps And Bounds Rather Than In A Smooth Progression."

Read MoreInformation Gallery by Amy Schichtel /

Jilting, squeezing, jitterbugging with the Parthenon, eradicating columnar calm and sending vertiginous blasts of gaiety and flux: that was Rifka's 80s.

Recently, formulaic grids overtook and subdued the disarray. The rational and the irrational coalesced into an essential vocabulary of materials and signs: linen, handmade paper, a Classical head, columns, the all purpose shape "a" and turtles. Framed by the grid, each contains newly found significance. With a new sense of clarity and her everlasting friendship with raw materials, Rifka is thoroughly immersed in exploring her rapport with this finite, but multi-leveled set of images and by extension, her rapport with the outer world.

Rifka is impelled to cut, feel and paste her chosen shapes. Palming them, she communicates with every morsel, and even though she places them easily, without preoccupation, each shape belongs where it is, as though it drove Rifka to its placement - indeed, as though she were the mediator and part of the medium herself.

Is she a psychic? No. In fact, Rifka hates to mysticize relationships. But, she is hyper-sensitive to the phenomenon of communication. Compassionately, she lives out a dialectic with our strange and estranged natural environment, and from this, her personal and artistic moments weave gently through one another. Turtles, for example, are among her favorite pets and have been added recently to her lexicon. She explains that to coexist with these foreign creatures, it was necessary to learn everything about them. Rifka tells stories and describes at length the necessary care for her pets. In the same antiheroic breath, she relays her artistic process. Understanding her rapport with nature and materials helps one grasp the content of her work.

In the studio, Rifka leaves scraps where they fall to literally surround herself with her medium in all its new, old and reformed states. After years of working, contemplating and touching them, she intuitively absorbs for use what various juxtapositions relay. For example, the chatty shape "a" was found in the negative space left in a sheet of paper from which many circles were cut closely together. Acquisitions like this, though, are rarely just gifts. A serendipitous discovery does lead to deliberate acts to save that moment. However, it is her sensitive, use-based inclination to save that allows for these accidental finds and for meanings to take shape.

The relationship Rifka has developed with her medium allows the whole a voluminous voice. Taken in its entirety, her wall installation, for example, creates an eidetic image. Still, it is easy to zone in on the digital flutter of the parts. Although more uniform than earlier compositions, the unevenly met squares of Bio File toss like lively rooms of conversationalists. The metamorphic "a"s, reading as "e" and "g"s, eagerly converse while the "a" on its back, as a waving little man, cries "halt" and "hello". The turtles pose in unison and the Classical heads dumbly stare, aloof. Regardless of their mannerisms, however, each remains alone in its own square universe.

The form of these vignettes is sculpted as much as drawn as it was in Rifka's stacked canvases of the early 1980s. The bark paper of her recent collage is thickly layered. The edges curl up and spread from one another like well worn pages.

Rifka permits the medium to speak as much as possible without interference. Nevertheless, she knows when to interrupt. Double Negative is white on white and fragmented, in some cases clearly the salvaged refuse from another cut. The parts look quasi pressed together in a hurried, careless manner. Yet, Rifka has allowed three rounds to glaze the surface, anchoring as if magnetic moons.

Rikfa's work has evolved over the years. Yet, she never stops culling through her past. In Sculpture Fragments with Column V. heads are cracked by "a"s and columns cut into their brows as though remnants of the upheaval from Rifka's earlier "History of Sculpture" series. But, the forms no longer surge. Thought bubbles of columns fill serious, empty heads and Delaunay-like prismatics make interceptions with line and form.

As Rifka's language is open, an appealing ambiguity persists. The mesh of heroic, Classical images with the folksier turtles and "a"s imparts a sense of down-home universality. Despite the interactivity, the selected images seem at once self-assured and introverted. The Classical head looks inwardly with its anticipated calm and self containment. The confident line striding the turtle's circumference suggests a firmly crusted, but protective shell. It is only Rifka's invented "a" that overtly expresses energy and curiosity. The signs become imprints of duration: duration of the mind, of the earth and of the evolving creative idea.

After years of rumbling through ancient history, Rifka is on the move toward an harmonious balance of being.

Corinthian Crackerjacks & Passing Go by Robert Pincus-Witten /

The conflict that vexes abstract painting in the late Eighties may be seen as a struggle between the ambitions of high art and those of popular culture. As these polarities collide they are driven further apart; or, at least insofar as Judy Rifka's painting is concerned, they are assimilated one to another.

Judy Rifka's painting is an emblem of this paradox. After all, the present-day subversion of faith in abstraction was promoted, not to say generated, by the community of artists amidst whom Rifka first emerged. Thus, beyond pleasure in painting itself, Rifka's mission has now become that of receding those very signals and signs that had undermined the prestige of abstraction; and, in so-doing, the restoration of our strained belief in transcendence is allowed to take place once again.

Rifka effectively mediates these antinomial fusions, this post-modern alchemy, through an extravagant ostracism of hierarchy. There is her acceptance of Constructivist and Expressionist values as an act of simple faith. This is clear, for example, in her method, the use of thin layers of grayed, milky acrylic paint, laid down adhesive tape-like, one over the other. With careful scrutiny, these layers are visible despite their often close graduation of tint let alone their extreme thinness. Such an examination adds to the pleasure of grasping and, in part, recreating the process of the development of the painting itself. Nothing could be more modernist in nature.

Rifka's commitment to process and discovery, doctrine within Abstract Expressionist practice, is of paramount concern though there is nothing dogmatic or pious about Rifka's use of the method. Playful rapidity and delight in discovery is everywhere evident in her painting.

Such rapid shifts are open to aphorism when glanced by Rifka's quicksilver turn of mind. Small daybooks testify, for example, to the heated production of the History of Sculpture, as the current work is known. They reveal her instrumentalization of the seemingly accidental. "Tremendous amount left to chance," she notes. "Recognize opportunity and Do it." Similarly: "Include imperfections in a deterioration process- Leaving beginnings to chance then shifting them till you see something you've never seen before But that somehow seems to express the moment."

Rifka's modernism, fully realized in the extraordinary abstractions she painted in the Seventies, were countered, this past decade, with ironies about popular culture though, for sure, this ambivalence is, in part, generated by the immense love she feels for the dubious article and kitsch in the first place. Characteristically, symbols of high culture are rendered as diagram, as felt-tip pen drawing of "the art of the ancients,"-the Nike of Samothrace, say, or entablature diagrams illustrating classical orders.

All this would be "high class" were it not for the comic strip-like depiction. Camp sensibility italicizes and capitalizes; it renders exquisite the ambivalence inherent to the banality of the oxymorons uttered or depicted.

For sure, Lichtenstein's classical references must be accounted for. The assimilation of Pop Art to high art represents the pivotal challenge to the authority of pure abstraction as it mediates the most radical inversion of values. For both sides of the equation. Rifka's painting resolves, or at least attempts to, this divergence difference without a distinction. As with Lichtenstein, Rifka's thumbnail spot-illustrations owe much to the advertising agency, to commodity theory, to image repetition and brand-name recognizability-insofar as one is talking about classical monuments; and, of course, to Duchamp. "I do all my drawing on acetate thereby eliminating the ground," she said in the Documenta 7 Catalogue of 1982. Thus is Duchamp's mechanomorphic society invoked. He too set his imagery within an absolute transparent space. All that passes behind the glass elides with transient ground, freeing the painter from the servitude of merely filling it in.

Similarly, Rifka's imagery is derived from a rapid tracing of photographs of the monuments, a virtually off-the-cuff studio resolution that further distances the motif from the cultural significance ofthe original monument, further severs "the sign from the signified," a catchphrase now betraying a certain period enthusiasm. Rifka's references may be to high culture but their depiction flatly asserts the authority of popular culture. Athena Parthenon as take-out coffee cup; Athena Lemnia hairspray; Athena Parthenos insect aerosol; Corinthian Crackerjacks.

Originally, Rifka worked primarily in oils, eventually settling on acrylics. "The drying time of oils is so horrible and so No Working in Layers." These layers continue with profligate variety in the current paintings. The cutout, silhouetted in template, is snipped from ordinary household shelving paper. Primary shape, secondary shape, negative/positive interplay is achieved through inspired variation flat, reversed, inverted and so on. The application of the system suggests a musical parallel, the Bach Two-or-Three-Part Invention, for example: first theme, second theme, inversion of the theme, ornamentation of the theme, inversion of the ornament, etc.

This hyperactive investigation asserts Cubo-Futurist origins. The present paintings recall spiraling permutations that occur in etchings by Jacques Villon, the Chessboard, say, or the Lamps. Nor is late-Futurist typography and photography under Mussolini a farfetched comparison. Rifka also works with images of a classical origin. This source came to be abused by the Fascists for a propaganda that asserted the superiority of a mythic Italian past by way of muffling outrage against its claims to entitlement in the present.

Rifka's free use of imagery, be it classical or popular, undermines the pretended refrigeration, the purity of high modernist abstraction. "Why should you have to leave out the drawing just because you made an abstraction?" she asks. "It's about letting in another bit of information."

"Why are the works so gray?" I ask. "I'm good at drawing," Rifka answers. "The longer I can hold out on the color, the more I can demand of the painting."

Still, I take color to be the ground zero of painting. Rifka astonishes by her blithe astuteness, her cool:

"Color," she says, "It's Red, Yellow, Blue, with black and white. It's formulas. You take two strong complementaries and add black and white. It's good. It's formulas."

II

A dutiful, correct daughter, Judy Rifka studies as Hunter College. After two years she goes to England on summer holiday. She paints at sthe Chelsea Art School. She becomes, as John Lennon said, an artist in eher own write. She feels at home in Swinging London, as that distant scene is called. A friend of Donovan and Phil Ochs, she inds herself at the center of musical developments of considerable interest.

Two years later Rifka returns to New York City and enrolls at the Studio School. The sentimental pieties of the school appeal, its mythology of studio drudgery. Modernism is dogma, the authority of Cezanne's form, of Giacometti's pint-topoint in space, of Hofmann's Push and Pull, all are studied in prim ernestness. Rifka loves it Young painters always do.

Rifka's Monsters by Andrea Scrima, Published August 2011 /

1.

Older than civilization, and inaccessible to the conscious mind, there is a nameless fear residing in each of us, a beast that seizes the sleeping self the moment it wakes and realizes that it must face a reality alien to the one it has just been expelled from. I turn off the alarm clock and try to make sense of a rapidly vanishing dream; I recall the list of tasks to be completed within the span of a new day. I get out of bed and begin my routine, because I know that this will shoo the spook. It’s tricky, though; it leaps out the window and disappears into the day, the weather, the uninviting street outside. And then I need to don my armor to face a world whose threats I can only guess at—but first I check Facebook, wondering: is Judy awake?

Judy Rifka’s finger has always been on the pulse of the time; she’s one of the only artists I know who uses Facebook as a viable artistic medium. Not as self-promotion, not merely to post reproductions of studio work, but as a series of quotidian interventions directed at no one in particular and accessible to all her friends—an integral part of a heated, often hilarious ongoing discussion among a loosely gathered group of artists that came together a few years ago on Jerry Saltz’s wall. While many of us have since met in person, our life online persists as sleepy morning musings mingle with observations on anything and everything happening in the art world or the similarly inauspicious one beyond it. Hardly a day goes by when Judy doesn’t post something witty or weird or simply amazing: pictures concocted on a daily basis in front of her laptop screen for her ever-widening audience of Facebook friends.