1.

Older than civilization, and inaccessible to the conscious mind, there is a nameless fear residing in each of us, a beast that seizes the sleeping self the moment it wakes and realizes that it must face a reality alien to the one it has just been expelled from. I turn off the alarm clock and try to make sense of a rapidly vanishing dream; I recall the list of tasks to be completed within the span of a new day. I get out of bed and begin my routine, because I know that this will shoo the spook. It’s tricky, though; it leaps out the window and disappears into the day, the weather, the uninviting street outside. And then I need to don my armor to face a world whose threats I can only guess at—but first I check Facebook, wondering: is Judy awake?

Judy Rifka’s finger has always been on the pulse of the time; she’s one of the only artists I know who uses Facebook as a viable artistic medium. Not as self-promotion, not merely to post reproductions of studio work, but as a series of quotidian interventions directed at no one in particular and accessible to all her friends—an integral part of a heated, often hilarious ongoing discussion among a loosely gathered group of artists that came together a few years ago on Jerry Saltz’s wall. While many of us have since met in person, our life online persists as sleepy morning musings mingle with observations on anything and everything happening in the art world or the similarly inauspicious one beyond it. Hardly a day goes by when Judy doesn’t post something witty or weird or simply amazing: pictures concocted on a daily basis in front of her laptop screen for her ever-widening audience of Facebook friends.

Over time, a prodigious body of work has accrued. Images of gargoyle-like cut-out paper creatures titled “You-don’t-have-to-clean-up-this-mess guy” and “Mwahaha—Judy is, err. Bizzy” alternate with photographs of the artist herself: “Monday Performance Art. Sound of One Hand Clapping.“ Other images involve sophisticated formal inquiries, such as a series of deceptively playful triptychs on color: “Primary Red” begins with a deadpan image of Rifka, brush in hand and bathed in red light; continues with a close-up of the brush dipped in red paint; and ends in a bright red rectangle, while “Blue is Everywhere” presents us with Rifka holding up a Crayola crayon with a fat squiggly blue tail cut from colored paper; a close-up of the crayon with its snaky blue paper blob; and finally a rectangle of blue on finely textured paper with a gradated shadow extending across it: not the red rectangle’s Platonic ideal, but a framed segment of the tangible world.

It’s this less-than-perfect world that so much of Judy Rifka’s online art springs from, this precarious mixture of public and private that we enter into when we engage in social media. Some of the titles read like chapter headings in an artist’s book of survival: “For the Next Four Hours I Will Be Marking Papers”; “I Can’t Get a Thing Done with Your Constant Interruptions”; “Into the Soup for a Soupy Commute”; some are simply views from her window—the Manhattan Bridge in the snow, or at sunrise, or a group of children playing outside on Market Street below. Everyday life persists; seasons come and go. In a triptych titled “Ha ha ha ha,” a Rifka of stern mien holds up paper cut-outs of the words “Ha Ha” to the laptop camera’s ever-watchful eye—and already I have my daily dose of mockery to toss in the face of fear so that I might begin my day monster-free.

2.

Judy and I first became friends during a discussion over the multifarious forms of discrimination against women artists. These were some of the compiled stats we were looking at as we tried to identify the obstacles blocking the path to women’s success in the arts: while roughly half of all artists in the country are women, they comprise less than 2% of all solo museum exhibitions; 5% of museum collections; and only 17% of all gallery exhibitions. A mere 26% of the artists reviewed in art periodicals are women; and while they hold 60% of all MFAs and 59% of all Ph.D.s in the fine arts, women make up only 33% of the nation’s art faculty. Only 25% of the $25,000 NEA grants go to women, 30% of all Guggenheim grants. The list goes on.

Jen Bradford, commenting on the establishment story of art, wrote: “It’s always been a very narrow, linear project describing an imaginary sort of march forward.” Bradford goes on to point out that many women artists have continued to work in their studios without institutional recognition, while their male counterparts “have ended up doing something else rather than continue to limp along.” The distinction points up a core integrity: an independence from the capitalization of art. Unfortunately, the art hierarchy has taken the virtue as a justification for devaluing and marginalizing women’s art. Wrote Lauri Lynnxe Murphy: “Women’s autobiographical work is about ‘women’s issues,’ men’s autobiographical work is ‘universally human.’” Unsurprisingly, one of Rifka’s statements has since proved prescient: “Perhaps the cyberworld may democratize by circumvention.”

Recently, when I began reading through notebooks of mine from the early nineteen-eighties for a book-in-progress, I happened upon a few sentences I had jotted down in 1983 during a panel discussion at A.I.R., the first artist-run gallery for women, which was on Crosby St. at the time. The panel was on feminist art; while people were quarrelling over David Salle, the audience, most of whom were women, proved to be allergic to the idea of feminine or feminist art. Women artists wanted to be seen as artists, period. As I glanced through my notes, the following sentence suddenly stood out: “Judy Rifka said she never even realized she was making political art until someone pointed out that the subject matter was a woman and that she was in a triumphant pose.”

Which brings the discussion full circle. Decades later, whether through the cyberworld’s democracy of circumvention or not, Rifka is back—with a vengeance. In the 1970s, Rifka’s painting and video art delineated an unmistakable and idiosyncratic visual vocabulary, absorbing pop elements to create a new, postmodernist language that gave succinct expression to the downtown zeitgeist. She was a founding member of the artists’ collective Colab, and is closely associated with the emergence of graffiti art and the incipient Lower East Side scene of that time, including such artists as Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring, among others. In an eloquent essay of 1981 titled “Radiant Child,” Rene Ricard famously celebrated Rifka’s art; speaking of the influence her synthesis of form and style was already exerting on countless downtown artists, he concluded: “She could then be called a painter’s painter if feeding ideas to others is what painters’ painters do.”

3.

Judy Rifka has participated in two Whitney Biennials, Documenta 7, the legendary Times Square show, and over fifty one-person museum and gallery exhibitions, not to mention an array of group shows and an impressive list of international museum collections. Rifka’s works with three-dimensional stretchers have been featured on the cover of Art in America; recently, in an arrangement with the National Gallery, the Vogel Collection has distributed her works to numerous American museum collections. An early video piece, the 1980 collaboration “Slap Pals” with Julius Kozlowski designed to be played on video screens in New York City clubs such as Danceteria and the Mudd Club, was featured in a show of visionary video work at The New Museum. Rifka’s early exploration of this medium testifies to her intuitive understanding of how emerging media alter the paradigms by which we think and live our lives; it also anticipates her later appropriation of Facebook and the revolutionary effect it exerts on the way in which millions of people define their social interaction, the version of themselves they wish to present to the world, and—not least—their subjective sense of personal identity.

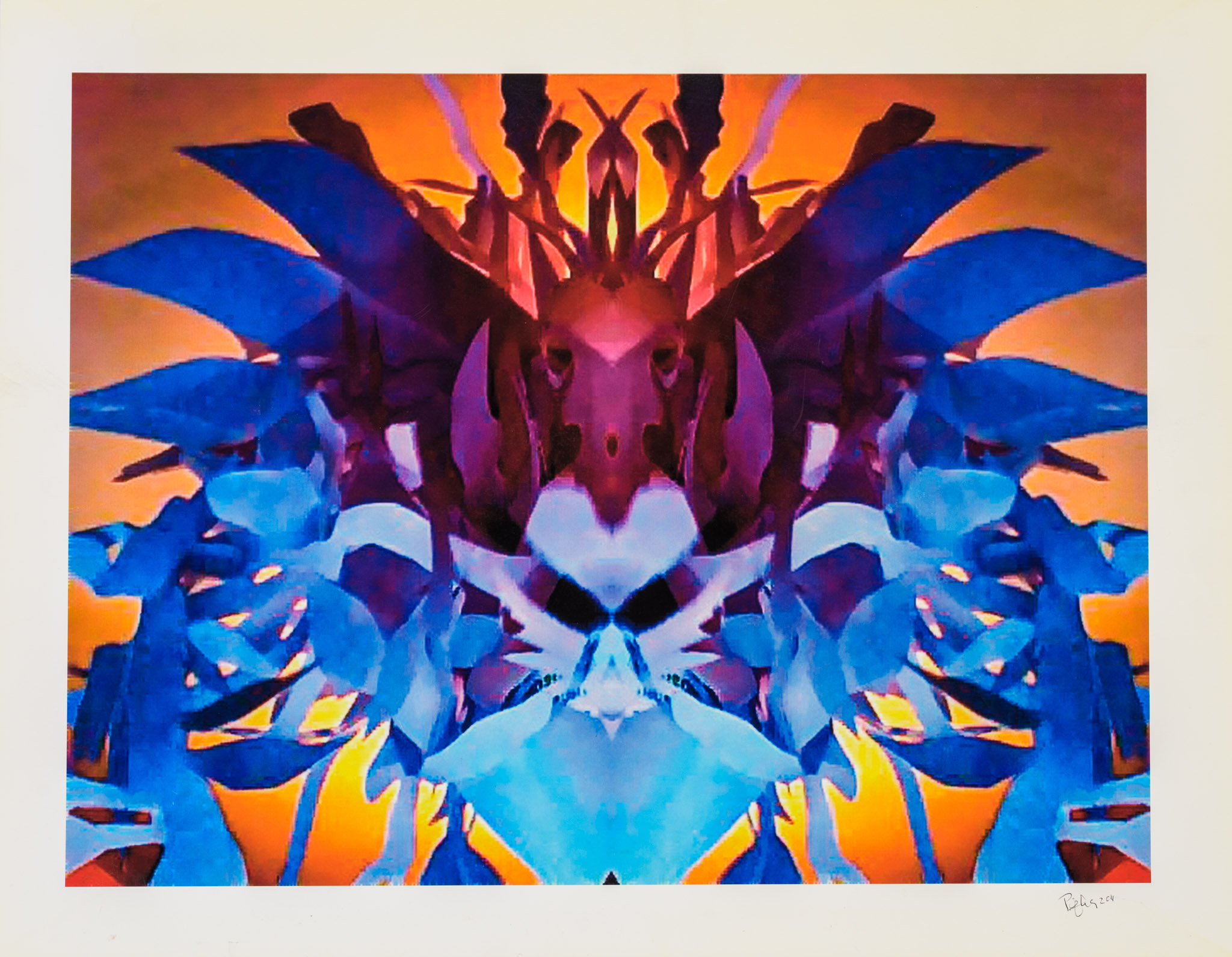

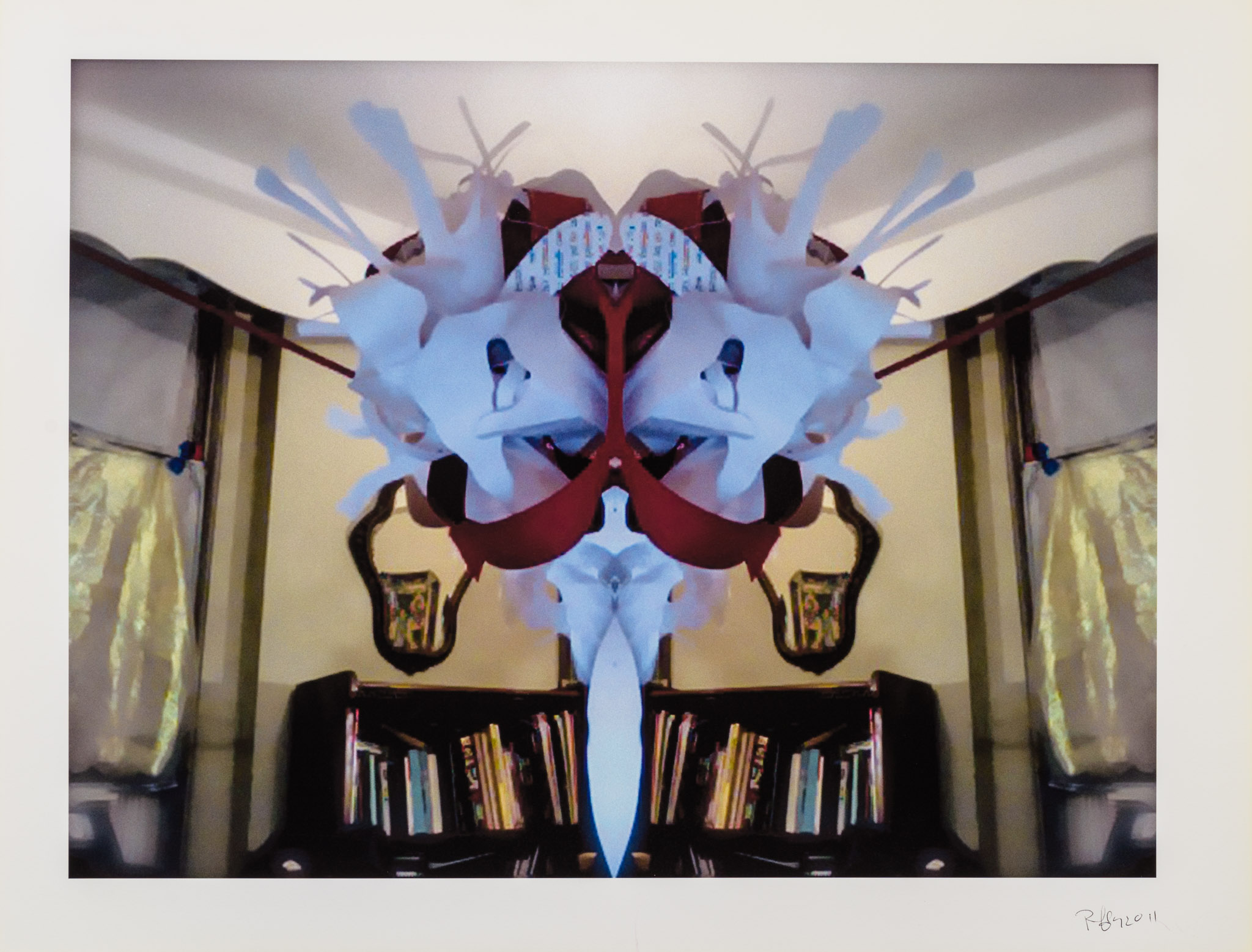

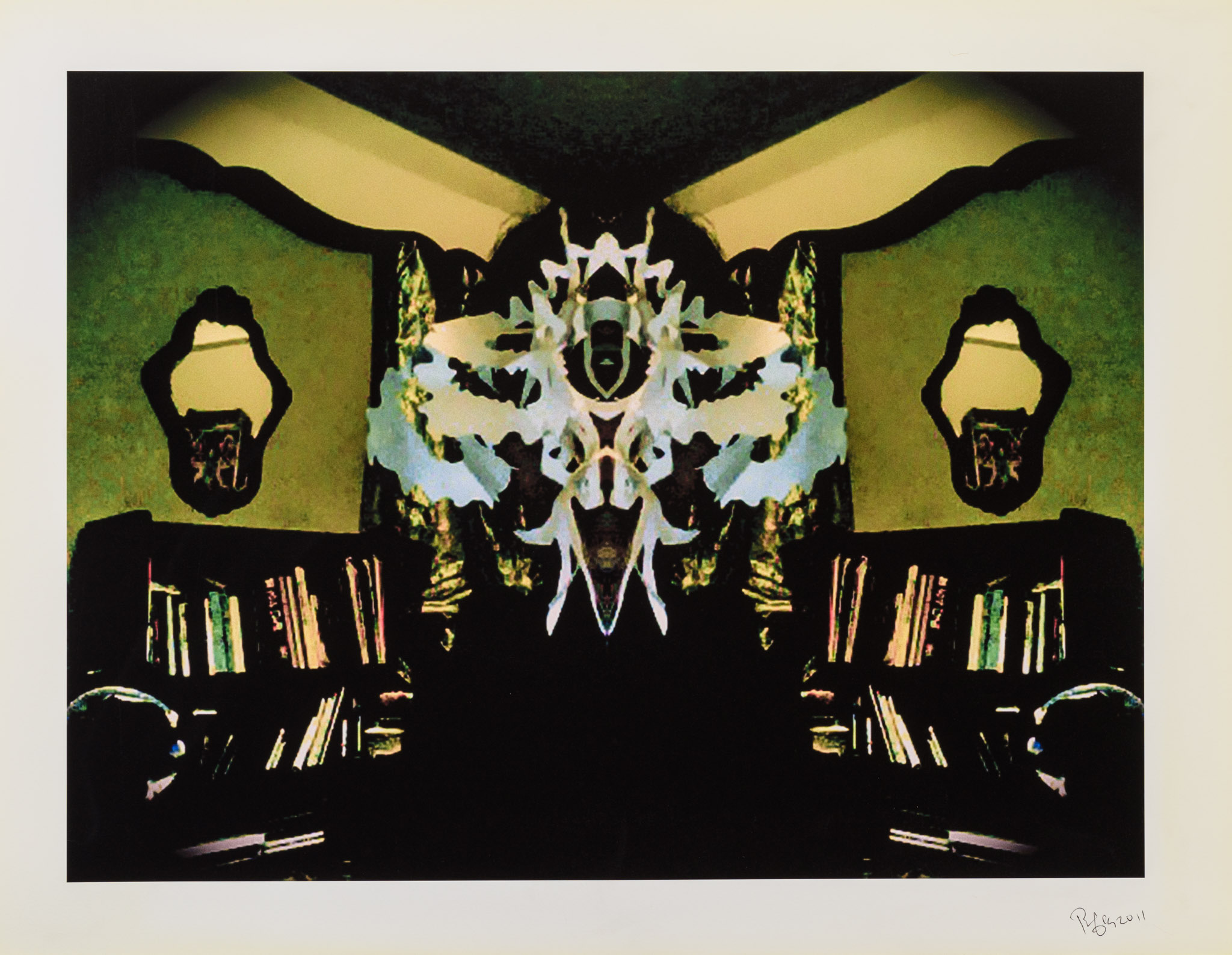

Judy Rifka’s poly-faceted paper images in the current exhibition at the Art6 Gallery derive in part from her extensive work with Facebook. Part insect, part architecture; part tangible, part virtual, they are hybrid creatures of this world and a realm beyond: godlike beings with tiny, sharp-toothed mouths and jagged-edged exoskeletons; incubi with throbbing thoraxes and jointed legs; ogres with multifaceted eyes and probing antennae. Rifka seems to take her creations through the various pupal and nymphal stages of metamorphosis and all manner of sexual and asexual reproduction, yet amidst these celebrations of mitosis and meiosis, the artist’s true mode d’emploi is parthenogenesis: she creates and recreates herself at will.

Rifka often populates her images as a dual being in mirrored reflection: a pair of Siamese twins joined at the wrist, the elbow, or the ear—a multiple personality trapped within the solipsistic logic of her very own Rorschach test. She is the hand holding up a corner of one of her paper creations or the camera taking the picture, or both. Sometimes the images are mask-like, hovering in symmetric suspension before backgrounds that bear traces of Rifka’s domestic environment: a potted plant, a bookcase, or the ever-recurring mirror on the wall—a sly aside to Alice, perhaps, or then again, just another part of the surroundings the virtual incorporation of which nonetheless transforms them into props hinting at clandestine ceremonies whereby Mandelbrot monsters bifurcate into hyperbolic components, grow tremendous in fractal proliferation, and smilingly invite us into their lair. And then we are called upon to provide answers to insolvable riddles to escape being devoured.

Rifka offers us daytime monsters; nighttime monsters; monsters in hues of purple, blue, yellow, and red cut from paper poised in an intricate balance between negative and positive space. When Rifka titles an image “Epiphysis cerebri,” the name given to the pineal gland regulating the body’s circadian rhythms and the part of the brain that Descartes held to be the “principal seat of the soul,” she provides an important clue to the origin of the beast. One key feature of the monstrous is that it defies intelligibility. We describe a thing as monstrous when we refuse to accept it as a part of being human, such as blood lust or sexual perversion; defining something as monstrous offers us a vent for the repressed emotions and drives we seek to banish from conscious thought and relegates them to the category of the alien. And so, as free-floating paper sculptures are suspended before pitch-black backgrounds and long afternoon shadows languish on the paper’s surface, we are brought back to the nameless dread that emerges on the threshold between the dream and the waking state—and are reminded that the powerful attraction monsters hold over us derives from the way they help us to escape our worst fears, which are always, overwhelmingly, of ourselves.